Yorkville, located between 3rd Ave. and the East River from E. 82nd north to E. 90th Sts., is renowned as a German neighborhood, but didn’t start out that way; from colonial times, it was a small settlement on the Upper East Side clustered along the now-disappeared Boston Post Road as it meandered north.

After the General Slocum steamboat crash in June 1904, nearly all of whose victims were German immigrants from the Lower East side, German as well as eastern European and Irish immigrants began moving to the East 80s; for many Germans, their previous home was too reminiscent of the disaster. There were greater opportunities to find work and new apartment buildings began to appear at the time, and there was plenty of mass transportation. Bear in mind that NYC had many trolley car lines and both the 2nd and 3rd Ave. Els were in business until 1940 and 1955 respectively. But the neighborhoods around the els began to dilapidate and age, and calls rang out to eliminate the els and let the sunshine in.

Social clubs and religious and educational institutions sprang up in Yorkville, creating and maintaining a network where German traditions were practiced and celebrated. Similarly, German restaurants, stores, beer halls, bookstores, and music venues guaranteed that German residents felt at home and outsiders and visitors felt immersed in German culture. Eighty-sixth St. was considered “German Broadway.” Since the 1960s, however, almost all of these German staples have disappeared, leaving little trace of the German culture that once defined the area. Post–World War II real estate development initiated a gentrification process that included soaring rents and often unwelcome high-rise buildings. A new and wealthier demographic meant that German businesses were forced to close.

It may be surprising to know that Yorkville was so-called at least by the Civil War era, and became more populated when the new NY & Harlem Railroad was built through the region in the 1830s. It was not named for York Ave., which received that name in honor of World War I hero Sergeant Alvin York in 1918.

Schaller and Weber, established in 1937 just as thousands of Germans and eastern Europeans moved into Yorkville, remains the foremost representative of the neighborhood’s former identity. Brand names that I remember from the German butchers in Bay Ridge are still here: Knorr, Maggi, Panni, Bechtle. I’ve always been fond of the German predilection for meals of meat, potatoes and vegetables, and German cuisine is unafraid of carbs (a meat & potatoes diet served my father well for 84 years). I’ll eat anything ending in -schweiger, -braten or-schnitzel. Located at 1654 2nd Ave. on the SE corner of E. 86th, the boxed candy, decorative steins, and sausages are displayed prominently. In season, S&W can obtain pretty much any kind of game meat. They continue the tradition of a free slice of baloney for every kid who comes in, which I enjoyed as a kid.

Photo: Nic Garcia

Next door is Heidelberg, one of the last restaurants in the area offering pure German fare (though there is still Zum Stammtisch in Glendale, Queens, and Killmeyer’s Old Bavaria Inn in Charleston, Staten Island). Morscher’s in Ridgewood has been gone for a few years.

If it’s boiled pig knuckles you’re looking for or the jaeger schnitzel, breaded veal smothered with a mushroom-cream gravy, served with spaetzle and red cabbage, Heidelberg’s the place.

Until early-2025, Five Mile Stone, a tavern on the corner of 2nd Ave. and E. 85th St. in Yorkville, was named for a marker on a long-vanished road that used to meander through the countryside in the Upper East Side.

The Boston Post Road, which followed an already established Native-American trail, was established in 1673 as couriers bringing mail to different locales in the colonies traveled the trail, which was then rough and interrupted in several locations. Couriers would mark miles by hacking cuts into trees at intervals. After nearly a century, the road was straightened and improved somewhat between New York and Boston, and from 1753-1769 heavy stone markers were set at one-mile intervals, with the surveying supervised by Benjamin Franklin. Postal rates were set by the distances between one spot and the other.

According to The Milestones and the Old Post Road (1915) by George W. Nash and Hopper Striker Mott, the Post Road’s fifth mile marker was formerly located at 3rd Ave. and East 77th St., but I imagine the bar’s proprietors figured this location was close enough. Just about all traces of the road itself have vanished in Manhattan, as the road fell into disuse in the early-to mid-1800s as the street grid system was built on the island from south to north.

There are only two extant markers surviving today in NYC. One is the 11-mile marker, which can be found on the grounds of the Morris-Jumel Mansion in Sugar Hill. Another is the 12-mile marker, embedded in the outside wall of Isham Park at Broadway and Isham Street. There are other surviving markers in towns like Mamaroneck and Hastings-on-Hudson.

On Delancey St. between the Bowery and Christie St., there’s a tavern called the One Mile House. The Bowery is an existing section of the Post Road, and the first mile marker was placed along the old road at about Delancey as it was one mile north of City Hall in the 1760s.

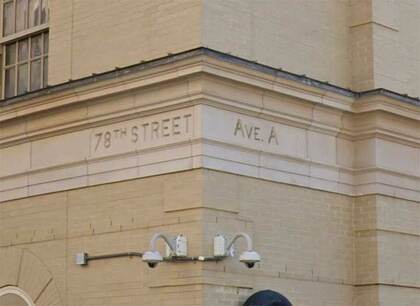

Why is a public school on York Ave. between E. 77th and 78th Sts. marked “Avenue A” on the York Avenue side? If you want to catch a glimpse of some former names of New York City thoroughfares, just look up at a building corner. One block east of 1st Ave/ is a north-south thoroughfare that goes by different names depending on what part of town you are in. Between E. Houston and E. 14th St., it's called Ave. A, but further uptown it's York Ave. and other names.

As originally laid out on the Commissioners’ Plan of 1811, formulated by a three-member commission made up of statesman Gouverneur Morris, lawyer John Rutherford and surveyor Simeon DeWitt delineating the orderly development and sale of land in Manhattan Island, it was Ave. A all the way uptown. Ave. A kept its name from E. 59th to E. 92nd Sts., until 1928, when it was named for World War I hero Sergeant Alvin C. York, who refused to accept any offers or endorsements based on his winning the Medal of Honor, saying "this uniform ain't for sale." He used profits from the 1941 movie biography starring Gary Cooper to open a school for children of his native Tennessee. York Ave.’s former name can be glimpsed on Public School 158, at York Ave. and E. 77th & 78th Sts., which still carries “Avenue A” on the York Ave. side.

A short piece of Avenue A was separated from the balance of its downtown stretch by another bend in the East River, east of 1st Ave. between E. 114th and E. 120th Sts. in Spanish Harlem. It was renamed Pleasant Ave., for its then-bucolic character, in 1879. Further downtown, pieces of Ave. A are now called Sutton Pl., Sutton Place South, and Asser Levy Pl.

The Yorkville Clock at 1501 3rd Ave. and East 85th St. has been here since 1898. Like many other sidewalk clocks it originally promoted a jeweler’s, in this case The Adolph Stern store. It was manufactured by the E. Howard Clock Company, and designated a NYC landmark by the Landmarks Preservation Commission in 1981. That didn’t prevent its temporary removal—in 1985, a city employee mistakenly sold the clock as surplus to a Long Island collector. The Koch administration tracked it down and by 1989 it was back in service, this time next to a McDonald’s. To celebrate its first century in service, in 1999 the pocket watch-inspired clock received a complete overhaul and has kept perfect time ever since.

Note that as with most clocks using Roman numerals, “4” is rendered as “IIII” instead of the “IV” used in original Roman script. The most plausible thing I’ve heard is that early clockmakers didn’t want people to mix up the IV and VI, so they substituted the IIII; and the tradition has stuck.

—Kevin Walsh is the webmaster of the award-winning website Forgotten NY, and the author of the books Forgotten New York (HarperCollins, 2006) and also, with the Greater Astoria Historical Society, Forgotten Queens (Arcadia, 2013)