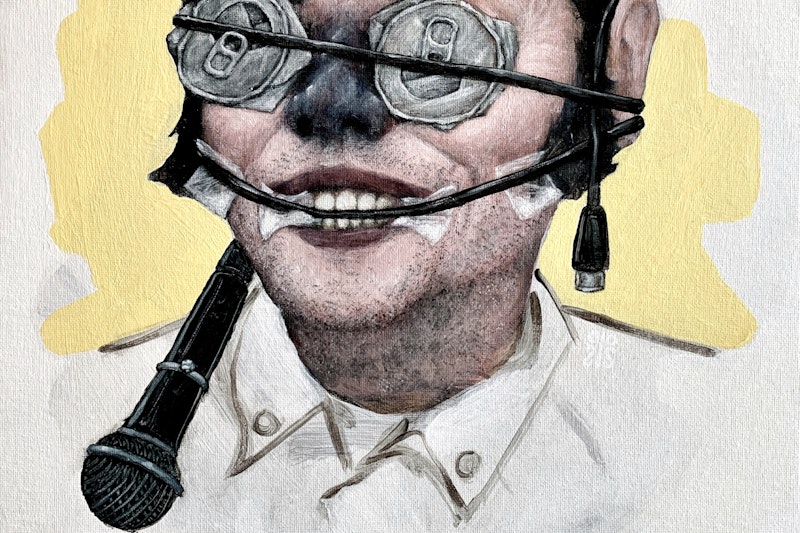

I haven’t done standup in over six months. Billy Ray Schafer, the protagonist of Running the Light, might say that’s a step in the right direction. Schafer’s a familiar type to anyone who’s ever done standup, an old road dog with no new tricks, chasing his Comedy Store glory days (the best man at Schafer’s wedding was Sam Kinison; his credits include 12 appearances on Carson) against a steady current of booze and cocaine. In terms of style and persona, Schafer combines the unpretentious working-class storytelling of Ron White with the defiant volatility of Doug Stanhope (both of whom praise the novel on its back cover). Schafer’s also a familiar fictional archetype: the fallen hero, his own worst enemy, who had it all but then blew it, now forced to star in his own depressing picaresque. We’ve seen this story before, but when it springs from the weird, dark, always funny imagination of comedian/first-time novelist Sam Tallent, it feels new.

The book takes place over the course of one November week, each night spent in some tiny venue in the American Southwest/Mountain West, frequently flashing back through Schafer’s memories as a standup. He starts in prison, forced by a guard to perform for hundreds of inmates (“I just flew in from Blue Pod and boy is my asshole tired”), opening for every movie night from then on. Schafer tramps through the past 40 years of comedy like a large, beer-gutted Zelig: the “Ex-Con Comedian Makes Good” puff pieces, his rise in the 1980s standup boom, the aborted stint as a writer for Roseanne, the messy divorce and subsequent plunge into addiction and obsolescence, each feeding the other, sending Schafer further into an abyss of what Paul Westerberg called “ashtray floors, dirty clothes and filthy jokes.”

Running the Light explores how working comics like Schafer rationalize their vocation, the alternately fatalistic and romantic view of the trade that all comics are familiar with. Every comic has joked about how doing standup comedy is mental illness, but that usually feels like a defense mechanism—a way for comics to save face by claiming to be in on the joke, the joke being that their need for adulation is some incurable chemical imbalance and therefore must be treated with stage time. It’s self-deprecation as a form of penance, very Catholic in a way—confessing with no plans to stop sinning, forgiveness with no strings attached. This is the shame cycle of Billy Ray Schafer’s life: self-absolution by means of self-disgust, hating himself so he can go right on doing all the things for which he hates himself.

This cycle is nothing new to working, not especially famous comics like Tallent, a writer who smartly sticks to what he knows: standup comedy; Colorado; being a “chubby behemoth”; driving hundreds of miles to play nowhere clubs and VFW halls; the loneliness of the long distance jester. He covers these topics with a literary acuity unusual in a profession perhaps best known for employing the unemployable. Kyle Kinane writes in his forward: “Sam created something the opposite of standup. He sat and wrote a piece of fiction. Standups, even the most disciplined, don’t do that.” While that’s patently untrue—I can think of at least four other comics off the top of my head who’ve written fiction—those who dabble in prose tend to be showbiz success stories who haven’t done standup in decades (i.e., Woody Allen, Steve Martin). To my knowledge, the only other working road dog like Tallent ever to write a book of fiction is Norm Macdonald, whose Based on a True Story remains the funniest fictional depiction of comedy ever produced. Norm’s a fairly big character in Running the Light, a former opener for Schafer who now generously offers him his scraps—15 minutes of show time—when he arrives unannounced during a sold out weekend in Denver.

Tallent’s imagination runs wild in these chapters. What would it be like to hang out with Norm and a grizzled old timer like Schafer—an “old chunk of coal,” as Norm liked to quote—after a show? How would the amiable Norm react if Schafer, say, smashed a beer bottle into an entitled SNL fan’s mouth? (“I too enjoyed that display of totally unwarranted brutality.”) What would they talk about during the quieter moments, alone in the green room or on a hotel balcony, those times when nobody’s trying to be funny? Writing in the voice of a beloved comedian, now gone but still alive at the time of the novel’s 2020 publication, is a tricky thing to pull off, requiring considerable attention to that person’s specific cadence, their speech patterns, their individual vocabulary (the first words Norm speaks in the book are “Good lord,” one of his go-to exclamations). It requires even stronger attention to their character and personality, to read between the lines of public persona and wrangle the human being therein. When Schafer turns on his former protegé after bombing a set, Norm’s reaction—a sadness and compassion for his suffering friend complicated by his own separate need to be onstage—feels at once surprising and, conversely, like the only possible outcome.

Schafer’s fallout with Norm is far from the saddest moment in Running the Light, a book filled with sad scenes, the most heartbreaking Schafer’s impromptu dinner with his son, with whom he hasn’t spoken in over three years. Their meeting goes from casual to tense to tender, interrupted by Schafer’s intermittent trips to the bathroom to do key bumps. The jaded comedian doesn’t seem shocked when his son tells him that his other son wishes he was dead, but when he tells Schafer that his older brother sometimes still sends him videos of their father’s TV appearances, like Ralph Wiggum, you can actually pinpoint the second when his heart rips in half.

The old cliché that dysfunction and depression fuel the comedian’s creative drive is only a cliché because, like all clichés, there’s some truth to it. Running the Light frequently flirts with these (the road-worn absentee father, the libertine entertainer, the old guard wandering an alien landscape of crass gentrification), and Tallent’s ability to dissect a badly-beaten dead horse and showcase its heart—that hidden truth, sometimes funny but more often heartbreaking—is not exclusive from his talent as a standup comedian. As artforms, standup and fiction couldn’t be any more different, but one thing they share is engaging an audience with words. What you say is usually less important than how you say it. “What he lacked in innovation he made up for in execution, tenacity and volume,” Tallent writes of Billy Ray Schafer. The same goes for Tallent himself.