Did you know there’s an “Edith Bouvier Beale (Little Edie) Appreciation Society” Facebook page with nearly 50,000 members? What is it that fascinates people about the story of Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis’ cousin, raised in a world of high society wealth only to eventually spend most of it aging in a dilapidated house in the Hamptons made famous by the Grey Gardens film, documentary, and musical franchise?

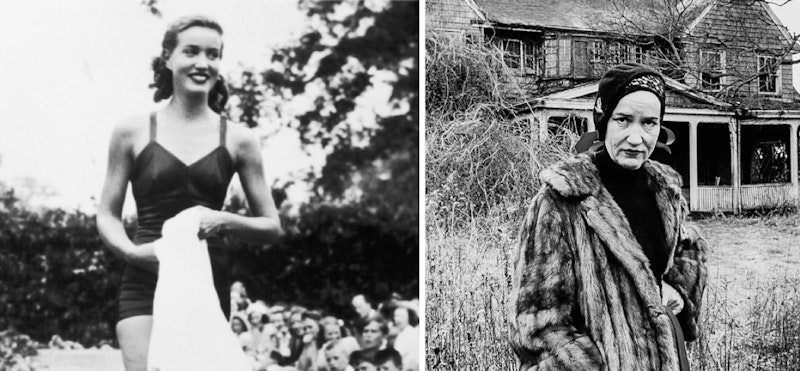

Edith (“Little Edie”) Bouvier Beale was born November 7, 1917 in New York City as the only daughter of Phelan and Edith Beale—she had two brothers who went on to have families, ignoring the fact that their mother and sister were living in squalor. As a young girl and teenager, Edie once modeled at Macy’s and lived the life of private schools, debutante balls, and summers on Long Island’s elite social circuit. She dreamed of being an actress, dancer, and singer, but her father disapproved. However, her mother created fake illnesses to pull her daughter out of school and keep the daughter she named after herself by her side.

When that wealthy father left, divorcing her mother (“Big Edie”) and leaving her without alimony during the Great Depression, Edith returned to the 28-room Hamptons mansion in 1952. The house was once a magnificent society retreat but now faced a dark fate. The events that occurred thereafter are depicted in the harrowing 1975 documentary Grey Gardens that depicts Edie and her mother living in the house, now decaying around them, overrun by cats and raccoons: roof leaking, walls peeling, gardens overgrown.

The film’s raw coverage exposed the women’s lives to the public, turning them into codependent mother-daughter figures of fascination and pity. Little Edie, with her headscarves and sweater brooches (that she called “the best costume for the day”), philosophically dramatic ramblings and unscripted dance moments, is a woman who rejected the rules of a society that abandoned her. Her personality, a mix of theatrical flair, humor, sorrow and vulnerability, elevated her to the status of a pop culture cult figure. Mental illness, though never formally diagnosed or discussed, is clearly a factor. Edie struggled with anxiety and depression as a result of the isolation; she suffered from alopecia totalis which is the reason for her iconic headscarves, despite a story from a cousin that she set her own hair on fire.

She speaks on film in a way that’s nostalgic and melancholy (but not bitter) about a life she’s missing out on—career, love, freedom—if not for the burden and expectations of caring for her mother. As the Women in World History page states: “She was a reminder of how easily brilliance can be stifled, how the pressure to conform can break a spirit, and how the things we love most can sometimes be the things that destroy us.”

In later years, after the city intervened and Jackie Kennedy spent money trying to mitigate the disastrous conditions in which the women were living, Edith finally left Grey Gardens, selling it after her mother’s death to journalist Ben Bradlee in 1979 (who restored it) and performing a cabaret in New York, but the damage had been done through years of isolation, the tangled relationship with her mother, and missed opportunities. She was haunted and died alone, her body not discovered for five days after death in 2002 at 84 in an apartment in Florida.

Her eccentric cult fame lives on, in the people who enjoy her fan page on Facebook and beyond. “It’s very difficult to keep the line between the past and the present,” as Edith once said, “You see, in dealing with me, the relatives didn’t know that they were dealing with a staunch character—and I tell you if there’s anything worse than a staunch woman… S-T-A-U-N-C-H. There’s nothing worse, I’m telling you. They don’t weaken.”