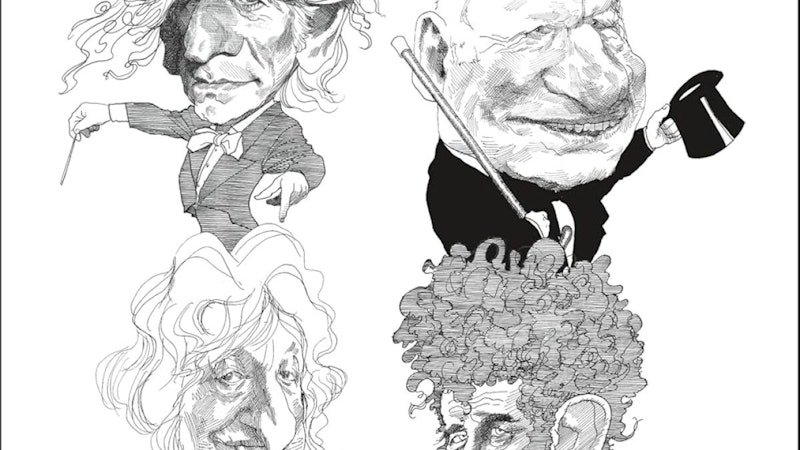

I’m currently working on a book celebrating Jewish contributions to American popular culture. It’s a celebration of Mad, Mel Brooks, Norman Mailer, Philip Glass, Annie Leibovitz and others. Yet there are also psychological and spiritual components to the book. America wouldn’t be America without the Jews. I wouldn’t be who I am without them. This is why I get so put off by the new antisemitism that has arisen in left and the right. To me it feels like a personal attack.

The reason why is explained, at least partly, in David Denby’s recent book Eminent Jews: Bernstein, Brooks, Friedan, Mailer. Denby argues that Jews who came to America allowed the culture to advance past the tribalism of old Europe and the places yet also have a vibrant moral vision. He writes:

But here’s the miracle, which I think of as a Jewish miracle: if their activities marked the end of tribal shame, it did not mark the end of conscience. A certain moral strenuousness emerged in all of them, an impulse toward exhortation and even prophecy. Some might find this laughable or hypocritical. In Yiddish: Ven der putz shteht ligt, der sechel in drerd, or “When the putz stands up, the brain goes to sleep.” By “putz” in this case, I mean ego in general. But the brain doesn’t sleep forever; it may even dream. I have taken their tendency to exhortation seriously as a natural impulse and a cultural demand. Jewish ethical ardency—the desire to make life better—got mixed into the bursting energies and claims of liberation; the combination of asserted freedom and ethical purpose ties them together as examples of a new kind of American Jew. Leonard Bernstein’s music making was part of a spiritual mission: if you could only hear Beethoven or Mahler, if you could only see how pain and pleasure were mixed together in ethnic gang violence, it would change you in some way.

This passage explains why I have such a visceral reaction to antisemitism. What Denby’s describing as the Jewish experience in America was also the Irish one. Like the Jews, the Irish—my people—wanted to escape tribalism while casting a critical eye on the alluring liberal culture that was beckoning to us. We wanted sex, freedom, James Joyce and rock ‘n’ roll, but were not necessarily down with socialism, promiscuity or atheism. We went to church but also loved Mel Brooks, described by Denby as someone “whose ego was robust, extensive, and unending. Mel was part of the larger Jewish influence that made public expression more candid, more physically explicit, and funnier. Every boy who realized that a fart was something to celebrate was in debt to Mel Brooks.”

In his book Catholic Modernism and the Irish Avant-Garde: The Achievement of Brian Coffey, Denis Devlin, and Thomas MacGreevy, James Matthew Wilson exports the tension in Ireland between Catholic traditionalists who followed William Butler Yeats and the modernists who favored Joyce. Like the Jews, we wanted modernism without losing a moral center. We wanted fun but not communism or the Holy Rollers. We avoided both Antifa and a humorless tight-ass like Matt Walsh.

In his great book We Don't Know Ourselves: A Personal History of Modern Ireland, Fintan O’Toole explores the modern Irish position between tradition and modernism: “The single most important aspect of Irish culture in these decades: the unknown known. Ours was a society that had developed an extraordinary capacity for cognitive disjunction, a genius for knowing and not knowing at the same time.” This describes Judaism just as well.

Like the Jews, Irish-Americans charting a new course between old world and new turned out to be right about a lot of things. Denby: “As they liberated themselves, [Jews] became sages, secular rabbis without shawl and tefillin, exemplars of full-bodied, fearless life, unrespectable but still demanding the utmost of themselves and other people. Though assimilated in many ways, they were not, as descendants of Russian and Eastern European Jews, entirely tame (unlike some of the German Jews). The Eastern Jews would continue to prize the qualities of temper, humor, and fantasy characteristic of their forebears.”

Irish-Americans were doing the same. Sinead O’Connor was right about the abuse in the Catholic Church. Joyce was right about the freedom of artistic expression. We had Jewish friends and girlfriends and were ahead of the changes that would happen under John Paul II, who fought harder than any pope to fight antisemitism. We knew babies being “in limbo” was ridiculous, and the Church changed the teaching.

Denby also mentions Mad, which created a template for modern American humor. Denby writes that Mad, “which was started by four Jewish boys in 1952,” was “a semi-scurrilous, all-out attack on propriety that became enormously influential on the counterculture that emerged a decade later.” That’s true, but as the critic Adam Gopnik observes in an essay in the book The MAD Files: Writers and Cartoonists on the Magazine that Warped America's Brain!, one of the founders of Mad was a Republican. Mad lampooned hippies and liberal Hollywood as much as it did the rest of American culture. While most people now view Mad as “the companion invader of rock ’n roll” and “a kind of bacillus resisted by the bulwark-like immunities of American conservative culture,” the magazine could cut both ways.

“In fact Mad satire posits a realm of sanity and obvious order for which some current craziness has emerged,” Gopnik writes, “and its purpose is to redirect the flow into normal sanity. Its purpose is to make us aware of the absurdities of what has come to seem normal.” It’s why Mad was criticized by the right for fueling the counterculture and by the left for its Brokeback Mountain parody, “Barebutt Mountain.”

The early punk scene was filled with Jewish artists: Iggy Pop, Sylvian Mizrahi and Johnny Thunders of the New York Dolls, and Lou Reed, often referred to as the “Godfather of Punk.” Joey Ramone, Jewish frontman of the Ramones, once said: “To me, punk is about being an individual and going against the grain and standing up and saying, ‘This is who I am.’”

Steve Bebeer, author of The Heebie-Jeebies at CBGB’s: A Secret History of Jewish Punk, wrote that “punk reflects the whole Jewish history of oppression and uncertainty, flight and wandering, belonging and not belonging, always being divided, being in and out, good and bad, part and apart.”

Leonard Bernstein, one of Denby’s subjects in Eminent Jews, once, according to Denby “put young American composers on notice, saying, in effect, ‘Don’t give up on beauty. If you are going to embrace serialism and atonality, you had better possess as strong a lyrical streak as Schoenberg and Berg.’”

By the 1980s “atonality and serialism had lost their grip, and composers were reaching for a more immediate and emotional connection with music lovers.” In his book The Rest Is Noise (2007), Alex Ross “traces the many branches of new music after 1980 to Bernstein.” This included Philip Glass, my favorite modern composer and a Jew who is more American than Candace Owens ever will be.

In We Don't Know Ourselves: A Personal History of Modern Ireland, Fintan O’Toole celebrates the modern Irish way of being moral people who aren’t enslaved by the past: “Perhaps we are learning to live without being so defined. An island capable of living with uncertainties, mysteries and doubt without reaching after fictional certitudes. The ambivalence was in us and in our political culture, in our ability to be amused at our own follies, in the sense of ourselves as a nation of nod-and-winkers. When you are winking, you have one eye open and one closed, and we hadn’t yet decided whether we wanted to look at the country with both eyes open.”