“For a while, it seemed like you were always seeing movies where all the music was determined by the music supervisors and their special relationships with certain record labels. And I just felt like, ‘Wow, I’ll bet they spent months or years writing this screenplay, and I’ll bet they spent months shooting this, and I’ll bet they spent months editing this, and now they’re spending no time at all picking these completely inappropriate songs with lyrics to put under a scene that has dialogue.’… Not only is that a crime, but it’s a crime not to give people who are good at making music for movies the work. It’s like saying, ‘We don’t need you, even though you’re so much better at it than I am as a music supervisor.’ Like the cancer that is that Darjeeling guy… His completely cancerous approach to using music is basically, ‘Here’s my iPod on shuffle, and here’s my movie.’ The two are just thrown together.” —Will Oldham, Interview with AVClub

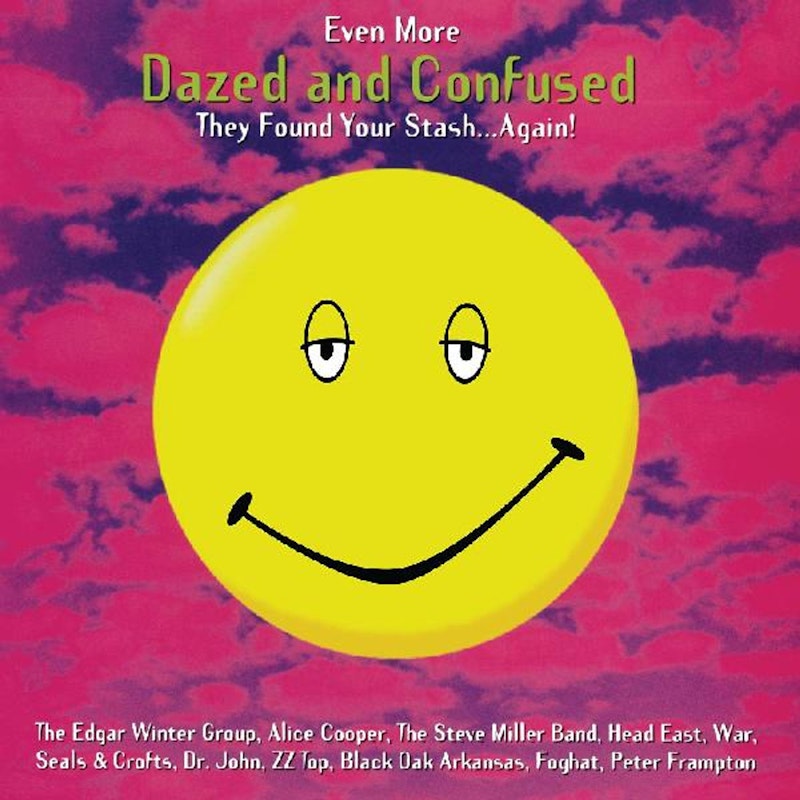

A good needle drop is tricky to pull off. Great movies like Dazed and Confused and Goodfellas make it look easy. Watch Randy “Pink” Floyd and the gang stroll into the Emporium to Bob Dylan’s “Hurricane,” or the gradual discovery of bodies set to the piano exit in “Layla,” and one could be forgiven for thinking they could pull off something similar, if offered the shot. But even setting aside the inspired incongruity of these soundtrack choices—a deadly serious harmonica-driven protest song about false incarceration playing during a teenage party scene, the gorgeous blend of Jim Gordon’s piano and Eric Clapton and Duane Allman’s dueling guitars laid over a dead goon tumbling inside a trash truck—the success of these sequences depends mostly on skilled editors (respectively, Sandra Adair and Thelma Schoonmaker) and the attention they pay to rhythm—as it pertains to montage (how this one short sequence is paced) and narrative (how the overall story is paced, and how the sequence fits in that story).

Notice the way Scorsese and Schoonmaker use those opening piano chords, inching up the grill of the pink Cadillac, slowly revealing the corpses behind the wheel, then rotating to the passenger window for the visual punchline—a blood soaked Monroney sticker—just as the guitars kick in. As a work of montage, it’s just about perfect: the way “Layla” gets lower in the mix during Ray Liotta’s narration and then goes back up to emphasize certain visual cues (Frankie Carbone hanging frozen in a meat truck, the car pulling into the garage). As it fits into the rest of the movie, the montage functions as a kind of elegy for the soon-to-be-departed Tommy (Joe Pesci). Even more than Tommy, it’s an elegy for the romantic, honor among thieves vision of the Mob (epitomized by the film’s titular line, narrated as Tommy kisses his mother and walks off to his death), an imaginary time when gangsters were outlaws bound by a code and not psychopaths who murder their friends. When that piano arrives, we know it’s the beginning of the end.

Yet outside the work of filmmakers like Linklater and Scorsese (not to mention needle-drop master Paul Thomas Anderson, who always finds surprising new ways to use pop music in his movies), needle drops mostly signal a complete lack of imagination. The recent Super Mario Bros. Movie is an above-average kids movie—a visual feast of candy-colored world-building, with a nice (if underutilized) score that interpolates Koji Kondo’s original Mario themes—sabotaged by bad soundtrack choices. Oldham can say what he wants about Wes Anderson, but at least Anderson doesn’t cherry pick Jack FM favorites to appease some imagined Gen-X parent. With dozens of games’ worth of excellent Mario music presumably at Nintendo’s disposal, why do these music supervisors need to spend even more money licensing “No Sleep Til Brooklyn” (get it, because they live in Brooklyn) or “Take On Me”? Like a turtle shell to the tire, each of these music cues knocks the movie off track. (This doesn't apply to original songs written for the film, like Jack Black-as-Koopa’s piano ballad to Peach, maybe the only time in recent memory that a kids movie made me laugh.)

Lest I come off as a grown man who’s mad about The Super Mario Bros. Movie, it’s important to add that the Spotify playlist approach to music supervision is hardly unique to kids’ movies. Air, Ben Affleck’s Air Jordan origin story, took more or less the exact same approach as Mario: it’s set in the 1980s (or, in Mario’s case, based on a game from the 80s), so fill it with 80s hits, specifically ones that have been used in much better movies—like “Sister Christian” (Boogie Nights), “Computer Love” (Menace II Society), “Tempted” (Reality Bites), and “Time After Time” (Romy and Michelle’s High School Reunion). Pandering cues usher the viewer from one scene to the next, as if the story were too difficult to follow without these signposts. The result of this 80s pop overload is something akin to a stomach ache. By the time the credits roll, any sane person will want to turn on some old delta blues or Mozart or noise music, anything that doesn’t remind them of Ben Affleck’s perm.

For as much shit as TV catches among my more cinephilically-inclined peers, the best series are often way ahead of the curve in their soundtrack choices. Did pop music lend any 20th-century period piece (besides those made by Martin Scorsese and Paul Thomas Anderson, naturally) the same kind of texture that it offered Mad Men? (Of the many incredible episode-closing drops on the series, maybe none is more memorable than Friend & Lover’s “Reach Out of the Darkness,” hitting right after Don and Megan receive the news of RFK’s assassination, sitting at the edge of their bed in one of the show’s trademark tableaux.) Despite what Oldham says about songs playing in the background while characters are talking, I can’t imagine the standout scene from season six of The Sopranos, where the tearful Carmella (Edie Falco) talks to her comatose husband, without Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers’ “American Girl” at low volume in the background, the guitar solo peaking just as her monologue similarly crescendos. For a more recent example, Hootie and the Blowfish’s “Hold My Hand” playing low over the sound system, while Barry (Bill Hader) buys a gun like it’s a piece of jerky, is just one example of why Barry is funnier than basically any movie from the last decade.

The kind of diegetic music found on Barry and The Sopranos isn’t entirely absent in modern cinema. Two of my favorite movies of the last five years crafted cinematic parties around their extensive pop soundtracks. Turner and Bill Ross’ largely improvised Bloody Nose, Empty Pockets is like Dazed and Confused for middle-aged barflies, chronicling a Las Vegas bar’s closing night party to the rhythm of its jukebox. The vast soundtrack differs from Air’s pop overload mostly in its lack of calculation and resistance to any specific theme or time period. You get the sense that every song choice is the result of some cast or crew member’s jukebox pick. Everything from the Eagles to Gucci Mane to Kool & the Gang to Sophie B. Hawkins gets rotation, sometimes only for brief snippets before the movie cuts to another scene/song. (I have no idea if/how they licensed all this music.)

It’s also way more fun than Air, or just about any recent movie. I remember watching Bloody Nose, Empty Pockets during quarantine, when I was unable to attend parties in person, and it felt like the next best thing. The same could be said of Lover’s Rock, the second installment in Steve McQueen’s Small Axe series, which depicts an early-1980s house party in West London. The soundtrack is almost entirely composed of the subgenre of romantic reggae from which the film takes its title, but once everyone in the party is good and high, the DJs throw on a little dub. Lover’s Rock is a rare thing, a movie about the black experience that sidelines struggle and allows its characters to experience unadulterated joy, even as that joy is constantly under threat from both outside the party and within. When we see the trembling bass of Augustus Pablo’s “Minstral Pablo” bouncing off walls—visibly dripping with condensation—it’s the platonic ideal of a pop needle drop: not some narrative crutch, not some music supervisor’s idea of what the key demos want to hear, but a means of providing texture and feeling and meaning to the images on screen.

Here are 10 movies from the last five years that I think use pop music effectively:

—Den of Thieves (2018, Christian Gudegast)

—Mid90s (2018, Jonah Hill)

—Under the Silver Lake (2018, David Robert Mitchell)

—The Irishman (2019, Martin Scorsese)

—Once Upon a Time in Hollywood (2019, Quentin Tarantino)

—Bloody Nose, Empty Pockets (2020, Bill and Ross Turner)

—Lover’s Rock (2020, Steve McQueen)

—Licorice Pizza (2021, Paul Thomas Anderson)

—Red Rocket (2021, Sean Baker)

—Aftersun (2022, Charlotte Wells)