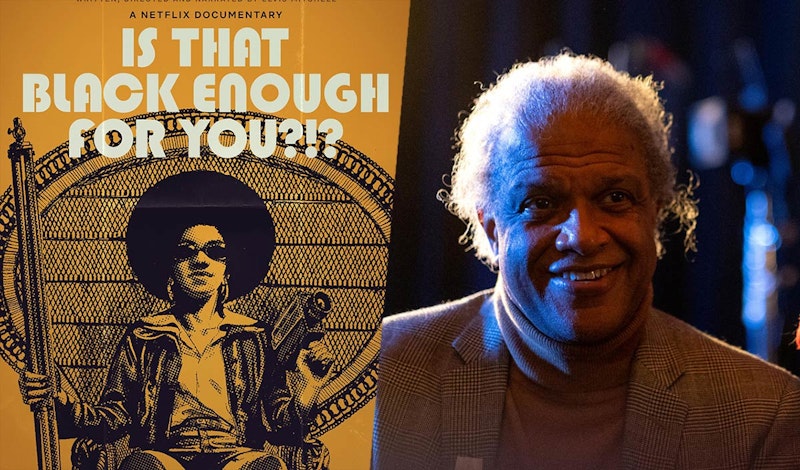

“No one wanted this as a book… no one.” Marc Maron couldn’t believe Elvis Mitchell on his show earlier this month, where the film scholar stopped by to promote his new Netflix documentary, Is That Black Enough for You?!? I don’t know the depressing ins-and-outs of publishing today, especially one of film analysis, but this documentary would’ve done well in arthouses and a handful of multiplexes this year, just like Questlove’s Summer of Soul in 2021. In an era of mass media white apologia, perhaps Mitchell’s film cuts too close to the bone, to the point where American studios and distributors—even relatively small ones—don’t appreciate the heat. But anyone who has even a casual understanding of Hollywood history could tell you that it took until 1967 for a black man marrying a white woman to be considered something other than a tragic aberration; even after Alfred Hitchcock introduced the flushing toilet in close-up to the American cinema, black actors like Harry Belafonte and Dorothy Dandridge couldn’t find work that wasn’t beneath them.

In fact, Sidney Poitier took some of those roles that Belafonte turned down: from 1959 to 1970, Belafonte didn’t appear in a film. “You know, I always had a destination whenever I went in for a meeting. So when they would give me shit I’d just give ‘em the ultimatum and say, ‘Fuck you, I’m moving to Paris.’” Poitier took the role that Belafonte turned down in Lilies of the Field, and he won Best Actor at the Oscars in 1964, the first non-white winner in that category and only the second actor after Hattie McDaniel won Best Supporting Actress for Gone with the Wind. “There’s a long-lasting narrative that 1939 was the best year for American cinema, but I cannot embrace any era that contains Gone with the Wind.” Mitchell deftly weaves film clips, archival footage, and new interviews with people like Belafonte, Whoopi Goldberg, Zendaya, Charles Burnett, Samuel L. Jackson, Laurence Fishburne, and Mario Van Peebles, among many others.

Without ever appearing onscreen, Mitchell examines the images of his youth, pulling no punches even against friends (Quentin Tarantino is featured in a quick cutaway when Mitchell’s talking about the absence of independent black auteurs being embraced in America, a moment that will probably make most people assume it’s a dig, without knowing that Mitchell and Tarantino are friends and two of our country’s foremost film scholars), and childhood favorites: “Watching old Hollywood movies, you’re often ambushed with offensive imagery, even from the masters.” This line plays out over a clip of a band in blackface… from Hitchcock’s 1937 Young and Innocent. Mitchell didn’t even have to go that far back to find examples of still-iconic stars in blackface: just the other night, I watched 1953’s Torch Song because Gig Young’s in a few scenes, and Joan Crawford has a huge musical number in Technicolor blackface.

Even more extreme is I’ll See You in My Dreams from the previous year, directed by master Michael Curtiz. Ten years earlier, he directed Casablanca; now, the famously prolific Hungarian was directing Doris Day in a huge blackface musical number, albeit set in the 1920s and, unlike Torch Song, in black and white, which just means the blackface is all the darker. Mitchell, like Tarantino with his recent Cinema Speculation, uses a guide through a certain strain of 1970s American cinema as a backdoor way through memoir, and though there’s far less personal information and anecdotes than Tarantino’s book or many other personal documentaries, Mitchell often invokes his grandmother, and what she said about movies, who was in them, who wasn’t, and what she might say if she were around today. Like so many movie lovers, he had that person influence him and instill that habit for life.

Movies are as good a way to view and analyze the world as any, and in my experience moviegoing has functioned a lot like religion, with a weekend routine, daily “checkups,” fluctuations in faith, and a mix of dubious, righteous, exaggerated, and outright false ideas, stereotypes, and values mixed into the sermon. I learned how to walk, talk, and sit upright by regularly watching mainstream American movies, and although I was born and raised in New York City, this is a common experience of many immigrants and minorities, even if they aren’t represented on screen. Of course I didn’t notice that some movies had no black people in them, I was white, they were invisible: Mitchell reiterates a point that can never be beaten into the ground, that it’s impossible for black audiences to take the majority of Hollywood cinema at face value for very obvious reasons.

But Mitchell’s one of the country’s best film scholars, and so his film isn’t the kind of one-note and one-inch-deep slander that you expect from charlatans now. Most people will think that Tarantino clip is an insult plain and simple, but to me, it’s the most powerful testament to what Mitchell is doing here, sparing no one: the fairy-tale success of directors like Tarantino and Paul Thomas Anderson in the 1990s is the bright side of the grim reality of independent black filmmakers like William Greaves, Gordon Parks, Ossie Davis, and Melvin Van Peebles, who were never embraced even when they made Hollywood millions of dollars. Otto Preminger may have pushed to end censorship in the 1950s and 1960s with provocative films, but even in his black romance Carmen Jones, Belafonte’s singing voice is dubbed by a white actor. Robert Downey, Sr. may have had to dub over Arnold Johnson’s entire part himself in Putney Swope, a last-resort move all too familiar to independent filmmakers. Although it was a practical rather than bigoted move, Mitchell notes that it must’ve influenced Downey’s son when he appeared in blackface in 2008’s Tropic Thunder, a role which he earned him an Oscar nomination.

Even seeing clips of Robert Downey, Jr. in blackface in a movie I saw when it came out is striking, if only for its high definition quality compared to most of the source material used here—to state the obvious, this shit isn’t over. Mitchell notes that while there are far more black filmmakers before and behind the camera in American cinema today, there’s still a century’s worth of racist residue left on the art form that he still considers the world’s best. This is one of the things that makes Is That Black Enough for You?!? so remarkable and exemplary now: a lesser critic and filmmaker could’ve made a version of this movie with little thought, care, or nuance, and at least attract some white investors and producers that want to cash in on this wave of white resentment and self-loathing before it recedes once again, but Mitchell’s too smart for that, and he loves cinema too much to blithely dismiss it and its history. At the top of the film, he says that, “My favorite era of movies is when the word ‘BLACK’ was in the titles,” referring to both film noir and black cinema of the 1960s and 1970s, from Belafonte and Poitier to Gordon Parks to blaxploitation and Pam Grier. Is That Black Enough for You?!? should be seen by any film student and anyone who wants to make a good mixed media movie with a wide scope and a deft touch.

It’s by some distance the best documentary of the year, and while it’s available on Netflix, it’s certainly not on the front page, even for documentaries—you have to look for it. I wouldn’t have known about Is That Black Enough for You?!? unless I heard Mitchell on Maron, a show I don’t listen to unless I really dig the guest. Whatever wins Best Documentary at the Oscars next year will be walking on feet of clay, because Mitchell already surpassed them with a movie “that no one wanted.”

—Follow Nicky Smith on Twitter: @nickyotissmith