If Lena Dunham’s Girls was the first work of art of the Millennial zeitgeist, and Joachim Trier’s The Worst Person in the World was the last, then we’ve entered the decade of their maturity, and while pop culture has, as always, moved onto people in their teens and 20s, Millennials will soon pry the rigor mortis hands of their Boomer parents from the levers of society and cultural production. Not everyone in my generation is yet eligible to run for president—including me—but in just two years, every Millennial will be over 30. And I’ve been waiting for everyone to grow up my whole life. The zeitgeist has moved onto Generation Z, and Euphoria is its first major work of art. As Millennials move into their 30s and eventually middle age, what will they write about? What are their obsessions? What are their grudges, tics, hang-ups? What will separate us from the triumphant Boomers and beyond cynical Gen Xers?

So far, the results are grim: Ari Aster’s third feature, Beau is Afraid, displays an empty technical virtuosity servicing a script that sounds like it was written in crayon. Aster’s a major movie buff, and he’s passed precocious imitation into the zone of professionals, real filmmakers: I don’t think this guy could make a bad movie per se if he tried. Obviously his first two films, Hereditary and Midsommar, were huge hits for A24, but they were clumsy at times (“Hail King Paimon”…?), and they were horror films that had bigger ambitions. Aster said he wrote Hereditary just to get a feature made, and now that he’s reached the level of success where trailers for your movie feature the tagline “FROM THE MIND OF ARI ASTER,” he doesn’t have to do genre anymore. This is a guy who’s favorite movie is Fanny and Alexander, so I’m glad he was able to ascend out of the gore pit of popular American cinema. Sam Peckinpah and John Carpenter, for example, never got out: the former would’ve rather made Play It as It Lays than Straw Dogs, and the latter wanted to make Westerns, which went extinct precisely when he began directing.

Aster, like Damien Chazelle, can do whatever he wants—or could. After the nine-figure failure of Babylon, Chazelle’s options must’ve shrunk, and although A24 happily bankrolled Beau is Afraid for $35 million, their most expensive production to date, I wonder how many doors will close, and if any will open, for Aster next week after the movie’s gone through the thresher of its opening weekend. Advance “press”—irate tweets, reports of people standing up immediately after and threatening anyone who “actually liked it”—had the counterproductive effect of making me see the first screening in Baltimore on its opening day, Thursday April 20. It was four in the afternoon, and the movie is three hours long, but there were only four other people in the theater. And after what I saw, I know there’s no way this movie is going to have the repeat business of Hereditary or Midsommar.

At best, Beau is Afraid is a display of Aster’s considerable abilities as a filmmaker, and if you ignore the script, you have a handsome movie. Although it’s clear Aster has studied the history of cinema, I’m not sure how much he reads; like last year’s Men, Beau is Afraid is a gender essentialist film, built on presuppositions that distinguish men and women completely. Every man in Beau is Afraid is a eunuch, just as every man in Alex Garland’s Men was a raving lunatic. Aster’s a better filmmaker than Garland, but they’re both stuck in the playpen when it comes to their scripts. A common complaint leveled against recent media is the overly didactic and unrealistic dialogue, talking points baked into a conversation. That same Millennial bluntness is on display here, as in the Daniels’ hugely successful Everything Everywhere All At Once, yet another “mad at mommy” movie that also served as an alarming indictment of Millennials and their concerns, abilities, and interests.

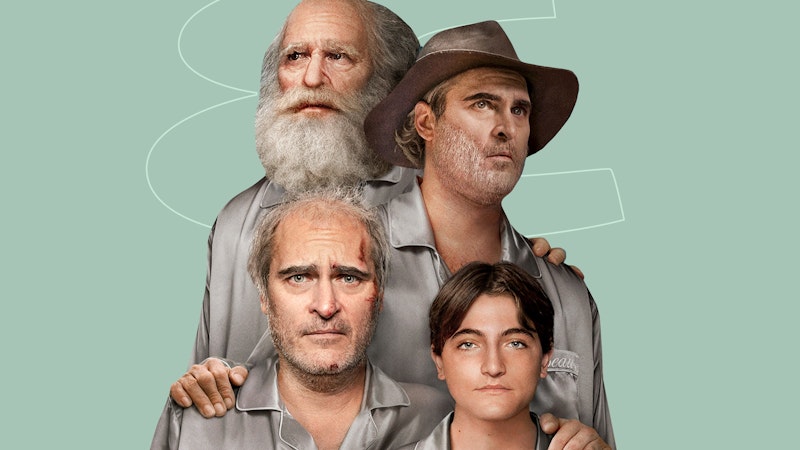

Aster isn’t sophomoric like the Daniels, but he has maybe one funny bone in his body, his actual funny bone, and baby, it’s small. The first half of Beau is Afraid plays like an expansion of the ending of Synecdoche, New York, when the world has fallen apart and Philip Seymour Hoffman is woken up by the sound of distant bombs and shouts. Here, Joaquin Phoenix is plopped into the thick of it, a Manhattan resembling that of Joker, full of violent schizoids and incompetent cops and wild-eyed vagrants. Everything from his perilous journey to buy a bottle of water across the street through the section at Nathan Lane and Amy Ryan’s house is gripping and well-made enough to mitigate the increasingly annoying and one note screenplay, but I lost all interest once Richard Kind showed up as Joaquin’s attorney, in a grand stadium full of people judging him, the final scene of the movie, when Joaquin is finally sent back into the water, the womb he so desperately wishes he could return to. Patti LuPone, his mother, just tortures him for existing.

Beau is Afraid is a Freudian movie written by someone who probably hasn’t read Freud. Or maybe Aster should just direct someone else’s scripts, because his words sink an otherwise interesting film. The inability to complete, the literal interpretation of the phrase “le petit mort,” all of the dead air dialogue—Millennials have a problem with poetry, a problem with grace, because it’s in so little of the work our generation has produced. Everything is spelled out, literalized, made clear and qualified, nothing left to mystery. Aster’s “Jewish Lord of the Rings” is nothing but a three-hour Buñuel riff, with an amusing cruelty that quickly becomes repetitive and hindered by Aster’s tiny, tiny funny bone. Any ire he receives from fans of his previous films, or women who will undoubtedly call the film misogynistic, won’t be because of the length of the film, its performances, or even its individual set pieces—this is a film with a script too amateurish to ignore, too obvious in its intentions and too stubborn in its monochromatic approach to extremely complicated issues, including but not limited to sexual anxiety, Oedipus, incest, Jewish guilt, and American dystopia.

This is a film that should be reckoned with, not tossed off with a glib capsule review about “mommy issues,” but just because it needs to be discussed, doesn’t make it any good. Beau is Afraid is another bad bellwether for Millennials and their abilities as they inherit the keys to the kingdom.

—Follow Nicky Smith on Twitter: @nickyotissmith