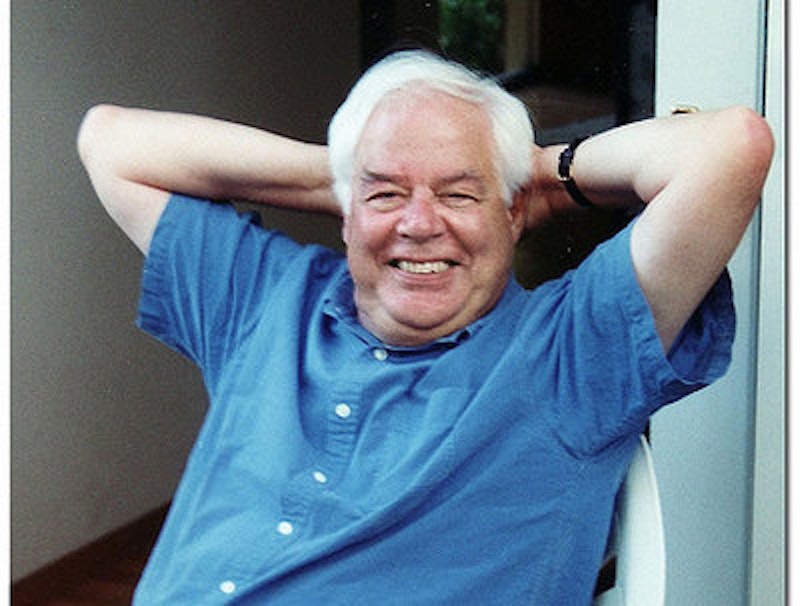

Richard Rorty, who died in 2007, was often called the most famous philosopher of the late-20th century writing in English. That's not necessarily impressive to the world at large, as most English-speaking people of the late-20th century probably couldn't have named a single contemporary philosopher. But within academia, he was as famous as anyone, which in his case involved being almost universally hated: both envied (he was the first and is still one of the few philosophers ever to get a MacArthur) and attacked relentlessly. The London Review of Books called him the “bad boy of American Philosophy,” which made him sound pretty intriguing: half Iggy Pop and half René Descartes. Ultimately, Dick Rorty became an emblem of postmodern relativism in the golden era of the culture wars, and was treated as a symptom of all that had gone wrong with the human intellect and the world in general.

In the early 1990s I saw him give a lecture to an auditorium full of eminent thinkers and grad students at the Society for the Advancement of American Philosophy. After he was done giving them his thoughts on pragmatism and truth, they fired away at him for the better part of an hour. Some asked questions. Most simply reviled him and everything he stood for, so hostile that they could barely express themselves coherently.

One person who attacked relentlessly was the quasi-celebrity philosopher Thelma Lavine, who had hosted the PBS series Socrates to Sartre. She was operating with a walker and an oxygen tank by then. I don't remember exactly what she said but the spirit was this: “You are enemy of all that is good and true, a philosophical anti-Christ here to bring our civilization to an apocalypse”: a last-gasp defense of truth and Plato and all things decent. After that, well-known philosophers came after him one by one or in gangs. He responded in clipped one-line provocations, half Jean-Paul Sartre and half Bill Belichick.

Later at the banquet I asked him how he got through things like that. He just gave the notorious Rorty shrug. "I've seen it before," he said. "They seem to enjoy it." It didn't seem to me like Lavine was enjoying herself, but Rorty certainly was.

He angered people as much by his insouciance as by his positions. Philosophers have spent millennia trying to formulate a good theory of truth. Rorty's approach? "Truth is what your contemporaries let you get away with saying." The formulation was almost a mockery: apparently casual, it gave rise to a thousand counter-examples, since one's contemporaries believe all sorts of jive. It was perfectly Rortyan in that without apparent effort it constituted a maximal provocation, and it made people think of Rorty as an arch post-modernist, relativist, or even nihilist. He came to symbolize an intellectual epoch.

He called himself a pragmatist and thought we'd better get busy trying to live with no god, no hard truths, even no world apart from the language we use to describe it.

He had an astonishing combination of cynicism and idealism, a quality he called "irony." One of his articles from the 1990s was called, with typical bold paradox, "Ethics Without Principles." He argued in favor of "liberal democracy," even as he declared that this commitment itself was a mere cultural prejudice and that he couldn't give any reasons, or wouldn't.

As an annihilating finale in his cannonade of academic calamity, he declared that philosophy was over or never existed in the first place and that we should write poetry instead. He claimed that the notions of “reality,” “the world,” or “truth” were boring and redundant or else oppressive and false.

His position was Socratic: you'd come to him with your big notions, essential ideas, revolutionary consciousness, scientific foundations and he'd use the whole toolkit from Willard Van Orman Quine to Jacques Derrida to let the air out of your tires. His most characteristic gesture was that shrug, accompanied by the hint of a shy and mysterious grin, as if underneath the pointed or even whimsical formulation there was a huge structure of ideas and arguments that he was holding back. As a matter of fact, there was.

Rorty was my dissertation supervisor in the 1980s at the University of Virginia. It took forever, which kept my family broke during my prime reproductive period. I'm still paying on the loans. But I did end up working with Rorty closely for five years and more. I wrote three completely separate book-length manuscripts under him about the philosophy of art of some of Rorty's heroes, such as John Dewey and Martin Heidegger. One problem in getting through was that in all three versions, it was dedicated, obliquely, to destroying my supervisor's philosophy.

Overall remark on the first version (I've got them all with his comments of course): “notably well written.” Richard Rorty was a pretty damn good writer for a philosopher, and “notably well-written” was enough to keep me going through the next version; I might have cared more about that than anything. Egads, I just realized I’ve spent my whole life reading some of the worst writing our species has every produced: both classics of philosophy from Aristotle to Hegel to Rawls and, most excruciatingly, the average new release from Oxford.

Anyway, that was definitely the high point (“there seems to be no coherence to this chapter—but simply a series of jottings,” etc.), though he was generous and fast getting stuff back with elaborate comments; he did it on the plane as he flew off to lecture in Beijing with Derrida or to Germany to debate his old buddy, the colossal Jurgen Habermas. Right when I knew him, Rorty was at his most meteoric rise.

One thing his many detractors didn't know was that he was always, semi-secretly, a sweet man, even to a young whippersnapper trying to refute him at every turn, and even as he became a loathed superstar with many demands on his time. As a thinker and writer, Rorty was a real swashbuckler, as bold as could readily be imagined, but one-on-one he was almost unbelievably shy. He found it terrifyingly difficult to greet people in the hall or at a reception, but opened up when happily absorbed in argument, and was completely or even maddeningly self-possessed in front of an audience. He was an extraordinarily gentle man but an extraordinarily aggressive thinker: really, quite the human conundrum.

Nevertheless, one of the most charming things about Rorty—as he showed in that auditorium—was that he delighted in attacks. He was some years past his breakthrough book Philosophy and the Mirror of Nature (1979) when I was working with him, and was drafting Contingency, Irony, and Solidarity, now widely regarded as his most characteristic work. One day in the middle of lunch in his office the phone rang and, as one did, he held up his hand and said, “Just a minute.” Then he launched into an elaborate description of CIS and a lovely assessment of how his own work was changing, how he was so far beyond Mirror of Nature, ready to kill the world. I hadn't known before that what he was working on. It took me 15 minutes to spin out that it was Rorty's college buddy, the equally eminent Richard Bernstein, on the other end.

Then he's off the phone and I start arguing with him about his “literary turn” nonsense. He didn’t respond to my attacks except to give me the in-process bibliography. I read it all. (I can't find that one. I must have chucked it when I was done.) But the most memorable thing about that phone call was that Rorty rummaged around on his desk and read aloud a couple of the most vicious criticisms of himself, as he and Bernstein cackled (cackling came through clearly on a land line).

Many philosophy professors thought he was careless or superficial, or that he was misinterpreting important figures or obviously reasoning fallaciously. True, one might’ve found bones to pick in his arguments, and he might often have given live audiences the impression that he was almost casually playing around with ideas and figures as he gave them that shrug, and that he thought everyone was taking all this stuff too seriously. But Lord the Rort had some critical acuity when he wasn't just shrugging at an auditorium full of people. He kicked my ass all day every day for years on end.

In doing that, he showed me exactly what the highest level of active intellectual life really is, what you have to know to toss off apparently casual provocations and make them stick; he slowly revealed how much machinery was underneath his performance art. I’d been reading harder than anyone I knew since I started getting serious at 12, but in my 20s in the 1980s I didn't see how knowing what he knew was even possible. He had more or less the whole history of Western philosophy and literature, with little pockets of expertise in all sorts of scholarly byways.

I thought he'd despise the followers who were trying to get him on their dissertation committees. But I thought that in disagreeing with him and attacking his philosophy I was emulating him: bold provocateur, bad boy of philosophy mark two. I thought he'd see himself in me as soon as I started disagreeing with him in an apparently casual yet highly provocative manner; just the right person to carry on. Looking back, I misunderstood how human beings work again. But at least I did really disagree with him: each iteration was an attempt to deepen, make irrefutable the critique. All indirectly. I didn't mention him except in the effusive acknowledgements. I did try to destroy some of his heroes—Hans-Georg Gadamer, for instance—on aesthetic matters: the image, representation, realism in the visual arts. I wasn’t ready to do that with any effectiveness.

While I was trying, Gadamer—the great, ancient German philosopher, Heidegger's student, author of that doorstop of hermeneutics Truth and Method—put in a surprise appearance in Rorty's seminar. We watched as Rorty and Gadamer sparred with great pleasure over Rorty's interpretation of Truth and Method, which we'd been receiving for weeks. Rorty summarized his take for 10 or 15 minutes. “Dick! Sounds great!" said Gadamer, his big eminent bereted head nodding. “Makes sense! But you've got me completely wrong!” Rorty laughed until I thought he'd cry, maybe a high point of his life, come to think of it. He came back with “Yes, Hans, but that's what you should have said." Then Gadamer started guffawing.

Anyway, it was oedipal; we actually heard a grad student say that one time as we walked around Cabell Hall. Rorty punched me on the shoulder. I thought he'd be delighted by my disagreement. He was, intermittently; we ended up having the best philosophical debates I ever had, through seminars, convention appearances, dozens of one-on-one hours. One thing he did clearly let me know: I was no Robert Brandom, who had been his student at Princeton and is now one of the world’s top philosophers. My first vague hint was sitting at the meeting with the big pile of paper = my second dissertation. He looked up at me with the half smile and said, “Well, you're no Robert Brandom.” Just going to admit it, I've been reading Robert Brandom enviously ever since, while never referring to his work. And I'll give him that, but who is an RB?

My best friend by the time I finished at UVA was a junior prof, and on my committee (well, I was 30). He reported the entirety of the deliberations led by Rorty after my defense: “If we don't let this one go, he'll just write another.” And that assessment, I'm also told, was reflected in his letter for me, long since abandoned along the road by pointed advice, never seen. I never wanted to publish anything from my dissertation or see it again. I swore I would, if nothing else, write the way I wanted for the rest of my life, and I pretty much have. I sort of blame him for the diss, sort of myself, sort of the whole grad school-type system. But one thing's for sure: I came out knowing a lot more than I did when I went in.

“Yo Dick, I found something we agree on! Carnap was totally wrong!” “Yup and he was kind of starting to see that when I studied with him.” Heavens! I’ve never even told some of these stories, because at meetings or even in friendships people only wanted to confront me about Rorty and how stupid he was. Then they didn't hear it when I said: Stupid? Definitely wrong. Okay you can be in our group! But you make no sense. Yes I do, man. I’m a disciple of Richard Rorty.

I've never known how to talk to philosophy people about Rorty or my relation to him. I told my non-philosophical romantic partners or whomever. There was no way I could talk about him honestly and make sense to philosophers. I've fidgeted through three-hour banquets where the people around me were ranting about how wrong he had Dewey, let's say. The next morning, it's at the coffee table. How did I just not run or attack? After that Gadamer thing, how do you take that?

So say you were listening to people spit the worst sort of bile at your mentor/greatest opponent, and the most they got to was the first couple of things that had occurred to you too and were too lame to even try on him? Right on, brother? Or do you expect me to sit here and engage in a defense? All through the 90s I tried a knowing smile. It was like I didn't even know Rorty. And then I forgot some of these stories or repressed them because that’s survival.

I did go on in my head trying to refute him. I turned the corner in my book End of Story, 10 years after I finished my Ph.D. It was quickly written and kind of disintegrated at the end. But I definitely wasn't worried about attacking the view explicitly after that. I had been killing it in my head for many years already; I wasn't really going to try the full 400-pager. No one was probably that interested anyway.

Despite the blows to my ego, no doubt highly necessary, Rorty one way or another taught me more than I thought I could learn. People didn't fully get this, but again he was incredibly erudite. I wasn’t going to win the argument when I was 25. Every week, I was trying to read everything so that I could arm up and encounter him as an equal on the field of battle, or the table of lunch. Or at least present him with something unexpected and get more than the shrug. My academic career has been a struggle ornamented with disasters, but the model persists. I'm 58, and it's taken all these decades to reach the point where I'm prepared to construct a picture of the intellectual terrain comparable to his. Now I'm ready to refute Richard Rorty, but he's gone and the oedipal struggle exists only in my mind, where all oedipal struggles exist anyway, finally.

Since Dick's death in 2007, there has been a notably positive reassessment of the man who was a dominant intellectual force of his era in large measure because he was unanimously reviled. I never heard a positive take on his work until the post-death tribute at the American Philosophical Association. I can tell the mood has changed because I'm not catching grief anymore for being his student, only curiosity. But I will not hear uncritical adoration either; that’s the deepest sort of betrayal of Rorty the person. And whatever the joys and burdens of being Rorty's student, I'll always be incredibly grateful to the man for myriad dimensions of my development.

I think he was wrong about everything, but at least he was wrong in an interesting and extremely bold way that was exemplary of its moment and helped create it. The academic philosophy of now, often hyper-specialized and extremely competent—isn't usually brave enough even to be wrong.

—Crispin Sartwell's book Entanglements: a System of Philosophy will by published by SUNY Press in March 2017.