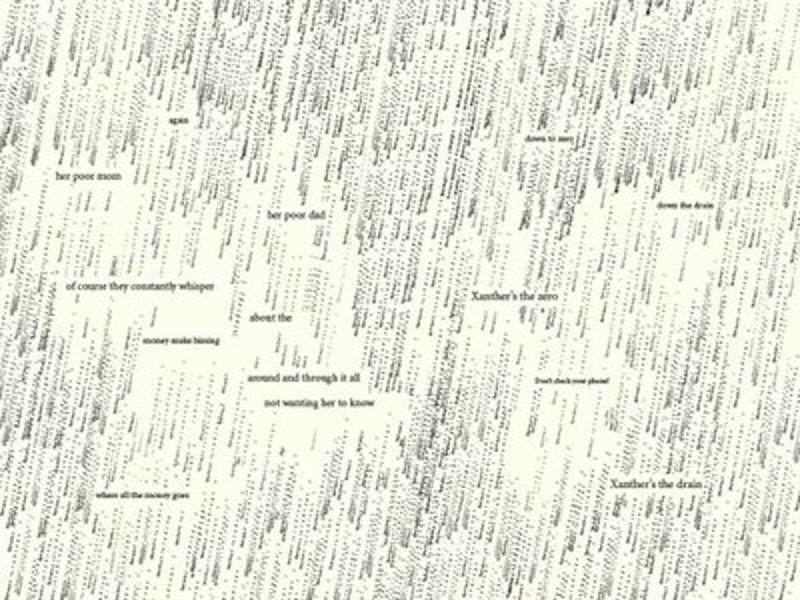

A white-text legend, superimposed atop pitch-black rectangles, flatly portends the end of history. “Stars are extinguished, collapsing into distances too great to breach,” it muses, adding “We are on either side of history: yours just beginning, ours approaching a trillion years of ends.” A tween girl, traveling with her stepfather in modern-day Los Angeles, becomes fascinated with a storm outside their car. “How many raindrops?” she wonders, her irrepressible curiosity splashing across two-page spreads, that question and others shrunken to microscopic point sizes, multiplied, plummeting in elastic diagonals.

The former is revealed as an excerpt from a fictional software program; in the latter instance, the tween is teetering on the verge of an epileptic attack. But no matter: in these first 90 pages of the first volume of The Familiar—his 27-part novel in the making—author Mark Danielewski treats twin, warring themes: entropy and infinity. The first two volumes saw release last year; with the third arriving in stores this June, it’s an ideal time to wander deep into an idiosyncratic, multi-genre universe that can at moments resemble sentient literary programming. Pink and black brambles limn inner margins. A cloth bookmark is sewn into every edition. Full-color illustrations and photographs pop between chapters. Chapter epigram selections range from Henry David Thoreau to GZA to Simone Weil to The Mamas & The Papas to Dr. Strangelove.

The narrative bounces between nine storylines, each stubbornly committed to a unique form. Danielewski’s primary avatar is Xanther Ibrahim, the aforementioned tween—precocious, awkward, withdrawn, troubled—whose epilepsy is perpetually a hair away from triggering. Her narrative is intertwined with those of Astair, her Ph.D. candidate mother, and Anwar, her video game designer stepfather. Elsewhere in L.A., gangbanger Luther Perez struggles to steer his crew clear of trouble; police detective Özgür "Oz" Talat, who broods in the style of the noir antecedents he grew up admiring, orbits a series of strange investigations; and Armenian cabbie Shnorkh Zildjian dies slowly.

In Mexico, cryptic, OCD fixer Isandòrno oversees the delivery of expensive cargo and drifts through an audience with his merciless employer. In Singapore, small-time criminal Jing-Jing cohabitates with and cares for an elderly healer. Aged computer scientist Cas and her husband, Bobby, crisscross the United States; they’re among a dwindling cohort of fugitives in possession of mysterious orbs that demand inordinate amounts of processing power to operate. In a running meta-fictional gag that evokes Thomas Pynchon and Wikipedia, “narrative constructs” (nar-cons, for short) offer readers helpful hints, cough up capsule biographies, and further deepen a prevailing crepuscular unease; much as many characters sense something supernatural is stalking them from just beyond the cusp of perception, readers sense some force quietly anticipating our questions.

And The Familiar is destined to inspire many questions, many of which may not be answered for years. In the first volume, the scattered cast is united—briefly—in reverse-Magnolia-climax fashion, as each detects the distant mewl of the drowning cat Xanther eventually rescues. But amid blunt, clever, and floridly elliptical prose far beyond what his celebrated debut House of Leaves promised, Danielewski lays traps and drops the broadest of hints. The ties that bind these protagonists are teased out slowly.

The sacred, spectral familiar of Tian Li, Jing-Jing’s housemate, vanishes from Singapore just as an ancient, miniscule cat washes into and upends Xanther’s life. Could this be the same animal? What does it mean that the text is starkly redacted in some areas and only loosely redacted in others? How do random hits of apparently ancillary bric-a-brac—bizarre instant-message exchanges, inebriated yahoos slaughtering animals, gothic comic strips—correlate to the larger tale being spun here? Why are there so many overt references to owls? What is the provenance of oft-mentioned narcotics packaged in blue, pink, and yellow balloons, of various lethalities?

A trio of corpses is discovered in a Long Beach home where a bedroom contains only computers, “domino-lines of black towers.” Is this crime in some way linked: to Cas’ power-thirsty, semi-omniscient orb; to the mysterious freelance debugging work Anwar does for an unknown client; to the “prank” a friend plays on Anwar and his family in which they’re deluged by texts, emails, and phone calls from strangers desperate to enlist in the military? Why can’t nar-cons translate Spanish to English?

En route to destinations that could double as answers, The Familiar swirls with considered, provocative imagery. How when Cas steels herself for worst-case scenarios, the movies she plans resemble role-playing game strategies. The way Astair’s thinking fractures into parentheticals upon parentheticals in an apt simulation of the endless tangents parental responsibility engenders. There’s the melody of Jing-Jing’s inner monologue, a Chinese-English hybrid presented in second-person, and Luther’s jaded thug-talk: “Most of the guys here, and there were only guys here, all Asian too, sat in white button shirts, sleeves rolled up past their elbows, a few shouting, some smiling, the rest just slouched over ashtrays and keyboard, like they methadone gripped, whatever key they tripped tying their accounts to cartoon horses and cartoon cards.” There’s Anwar, awake at dawn, interrogating impudent code as the sleeping house creaks malevolently around him; he’s a mirror, seemingly, of The Familiar’s own audience, straining through curated noise to detect hidden, subtextual signals.

An early chapter in Volume 2 epitomizes Danielewski’s deft facility for tonal juggling. Xanther emerges from a desolate, confusing nightmare to find her new pet ailing. She and her mother make an emergency trip to a veterinarian's office, where the cat is poked, prodded, examined, and scanned. A chip implanted in the cat identifies it as a dog. The visit slides through adolescent vicissitudes, from worry to fear to curiosity about vet supplies and a Cats of the World poster to a sudden bout of sickness. The staff exudes a warmth and care that the reader, through Xanther, knows to trust as warmly genuine; her mother takes charge, asking important questions, and the vibe feels warily upbeat. The chapter ends this way:

“And even if fun doesn’t quite fit, the tiny creature breathing softly in the cradle of her arms somehow settles Xanther. More than that. A kind of lightness follows, like even shadows lose their hold a bit, including the one thrown by the door as they hustle out onto Santa Monica Boulevard, or the one cast by their parking meter, maybe grayer?, or even the ones in their car, collecting around Xanther’s feet, as they head home.

“A dog!” Astair laughs as she turns left up Echo Park Avenue. “And in this area. And an Akita too. What are the chances?”

Which is funny, or at least smile-worthy, if her mother’s eyes didn’t look now like two black holes.”