The late experimental novelist B.S. Johnson belonged to a spate of mid-20th century British writers that never received stateside attention to match their reputations back home. Names like Henry Green, Anthony Powell, and Angus Wilson mean almost nothing to most American readers, even though they were some of England’s foremost literary lights for decades. Johnson was slightly younger than these writers, and his work’s relative lack of attention in America is perhaps the most perplexing. One would think that his aggressive stylistic innovation (in the tradition of his professed heroes Joyce, Sterne, and Beckett) would have been heralded by the same 1960s readers who propelled Thomas Pynchon and John Barth to the mainstream.

Case in point, his 1969 novel The Unfortunates, which New Directions Press has just made available in the U.S. for the first time. The Unfortunates took the late-modernist obsession with textual fragmentation to a new extreme: it consists of 27 unbound chapters which, with the exception of two labeled “First” and “Last,” are to be read in whatever order the reader chooses. The chapters range from one paragraph to 12 pages and are packaged in a cardboard slipcase as Johnson intended, the source of his novel’s reputation as the “book in a box.”

William S. Burroughs had long before acknowledged his collage method of writing, wherein he literally took scissors to his pages and randomly resorted the sentences. Johnson’s method was even more extreme, however, as it grants final control of the reading experience to the reader himself. The book is a first-person account of an English football reporter whose professional duties get sidetracked by constant thoughts of his friend Tony, who died of bone cancer. Regardless of what order the reader assembles these chapters in, however, the dramatic thrust of The Unfortunates isn’t likely to change; the writing is all first person, comma-heavy stream of consciousness. Each chapter typically corresponds to a specific recollection, such as the friends’ first meeting or the narrator’s late visit to the hospital, and while they contain beautiful passages individually, the novel’s power comes from their accumulation. Together, in whatever order, they form a dual portrait of the narrator’s attempt to write well about a dull football match, and the difficulty imposed on that goal by the haunting memories that accompany the match’s hosting city.

“The things Tony’s death throws up,” the narrator opines at one point. In his lucid and informative introduction, novelist and Johnson biographer Jonathan Coe explains, “It was this randomness, this lack of structure in the way we remember things and receive impressions, that Johnson wanted to record with absolute fidelity.” Coe is smart enough to also grant that, whatever theoretical coat Johnson wanted to hang on his novel, the “book in a box” idea was also a deft publicity stunt. Johnson might certainly appear to be flaunting traditional literary ideas for the sake of theories and at the expense of characters, but what makes The Unfortunates a great book (and its first American appearance a cause for celebration) is how well it refutes that categorization; it is that rare artistic experiment where the formal innovation is an artistically and emotionally necessary one.

It’s helpful to learn from Coe’s introduction that Johnson was essentially an autobiographer. The Unfortunates’ events all happened to him: the death of a close friend named Tony, a frustrating turn as a sportswriter, even the specific incident—stepping off a train into a sketchily familiar city—that prompted his idea for the novel. The narrator’s grief is not only engagingly written by any standard, but also more powerful for being intensely personal for Johnson. “I sentimentalize again,” the narrator says, “the past is always to be sentimentalized, inevitably.” The great trick of The Unfortunates is to watch sadness unfold messily, unsentimentally, in a structure that mimics the necessarily individual experience of mourning.

Try teaching this book in a class, or citing it in an essay. How do you direct another person’s attention to a specific passage, when no page numbers are offered past 12? (“Is this sort of experience good for students?” asks the narrator, answering, “No, surely not.”) Try reading it simultaneously with a friend, as would no doubt heighten the touching—and entirely unromanticized—reflections on friendship that Johnson offers. You’d be reading a physically different book as you technically read the same one, just as the narrator reflects that, “everything we know about someone is perhaps not the same, even radically different from what others, another, may seem or understand about them, him.”

That’s the theoretical bit, and it’s a grand slam, but The Unfortunates is also a generous book in its characterization and emotional engagement, two things that most experimental writers aren’t known for. That Johnson’s narration is actually his own internal wrangling only deepens the ambivalence and honesty of his novel. He selfishly remembers being upset when his dying friend couldn’t make it to one of his readings; he recalls that many of their conversations were actually quite boring; and he remembers Wendy, the girlfriend he had while first becoming friends with Tony, who had an air of sexual excitement now missing from his marriage to a different woman. And along the way, he tries in vain to write a decent sports column, in chapters that are funny and self-deprecating profiles of a man who thinks he can eventually write great books but for the moment can’t even crank out 500 words about the action on the pitch. It is an uncomfortably honest, wholly unpretentious autobiography where Johnson lays his various feelings out for us, as unbound and untidy as the book itself.

The topic of The Unfortunates may be grief (Johnson wasn’t a happy man, and he killed himself in 1973), but it’s not a particularly sad book; there’s too much truthfulness in its narration, too much generosity on behalf of its author. And the “First” and “Last” chapters are thematically fitting concessions to traditional form, since they force all readers to begin the memorial recollections with Johnson and then end the book with him as he returns home to his wife and son, content and warmed by their presence after 180 pages of emotional ambivalence. It feels like the way this book should end; we may mourn individually, but rarely alone.

The Unfortunates by B.S. Johnson. Published originally in 1969; reissued by New Directions Press in May 2008. 176pp., $24.95.

Grief in a Box

B.S. Johnson’s experimental novel is a collection of unbound chapters, so you can feel as sad as the narrator.

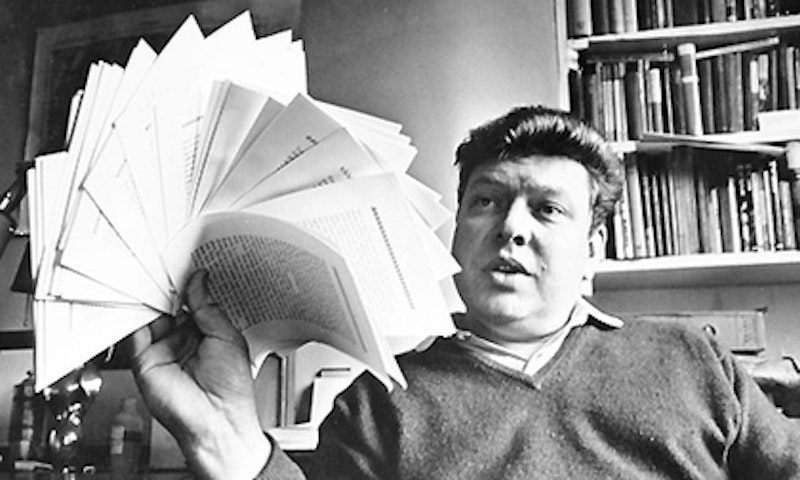

B.S. Johnson holds up a manuscript in the late 1960s.