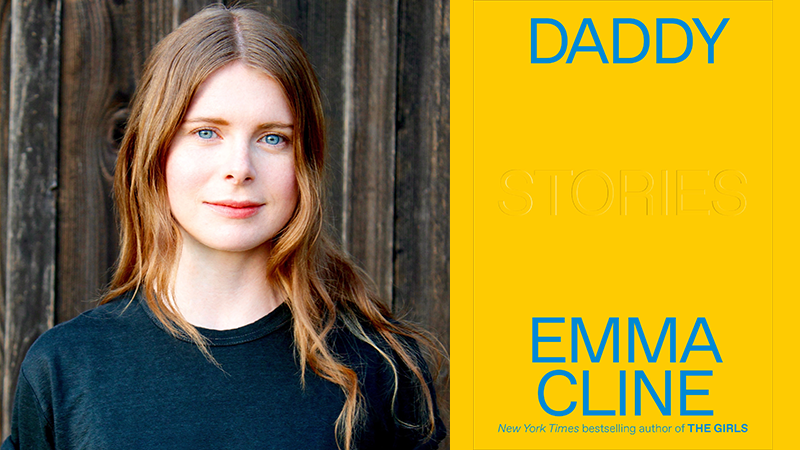

Emma Cline loves writing about food, smells, and physiology. Her recent story collection Daddy, out now in hardcover from Penguin Random House, is full of disgusting descriptions of “tangy breath,” “sweet child breath,” all manners of mucus and boogers, rotting gift baskets, bland charcuterie boards, and broken dishwashers that, “marinate the dishes in a stew of warm water and food scraps.” This is Cline’s second book, after her first novel The Girls, a huge hit in 2016. She’s hardly a “newcomer”: her work has been featured in prominent literary publications for nearly a decade, including The Paris Review (where “Marion,” one of Daddy’s weaker stories, was published in 2013), The New Yorker, and The New York Times.

Daddy is a good book, with some good stories—particularly “Northeast Regional,” “Menlo Park,” “Los Angeles,” and “Son of Friedman”—and it made me dig out the paperback copy of The Girls I meant to read nearly three years ago. I don’t know that I would’ve ever read this collection if I read that Paris Review piece above first, so precious and aloof, lacking any kind of edge or aggression that’s, at points, abundant in Daddy.

Cline isn’t as talented or interesting as Ottessa Moshfegh, for example, but they cover a similar territory of modern romantic horror: dashed expectations that were diminished in the first place. Cline’s characters in Daddy are hapless males ranging from early-20s to early-70s, and they’re all to some extent stunted in their adolescence: through the eyes of Cline, “these men who have clearly caused pain, but cannot absorb that fact into their self-narrative—it would be too dangerous and too confrontational to have to assimilate this information that they are getting from the people around them.”

It’s hard to trust anyone who talks like this, such a needlessly convoluted and vague way of describing men who don’t take responsibility for themselves or their actions. They’re not thinking in terms of “self-narrative” or what traumas and disappointments they may or may not be absorbing—as Cline writes, they swallow pills on Amtrak and live the lives that Nick Mullen once described so perfectly on Cum Town: “Boomers with property who take half a Viagra and listen to The Rolling Stones.” The patriarchs of Daddy are well observed while often feeling interchangeable and anonymous.

Only the fathers of “Menlo Park,” “Son of Friedman,” and “Northeast Regional” come off like real human beings, the sickos who raise sons and daughters to go to elite prep schools and elite colleges to get regular degrees that mean close to nothing. The first father, the daddy that used to hit, the papa of “What Do You Do With a General,” resigns himself to bad salami and going with the flow of his family, who hate and resent him. Younger “father figures,” like the lead in “Arcadia,” only 20, are similarly hapless and without a paddle in the “real world” because his moral compass and basic sense of right, wrong, and “how things are done” comes not from books, but not from parents either. The men in this book aren’t tethered to any kind of tradition or mentorship, and it’s left them disappointed and adrift, unable to wrest themselves out of vague despair.

“Northeast Regional” follows a former government official falling out with his latest mistress and taking care of the expulsion of his repugnant, impossibly nerdy son. Throughout Daddy, Cline elides incidental and crucial details and occasionally lets things slip when communicating her characters’ real inner loathing for their fellow man: Richard, the “daddy” in “Northeast Regional,” says of customer service in rural America: “This is why you lived in cities—abundance buffered you from the vagaries of human contact. If this had happened at home, Richard would have got out and grabbed the next cab. But here was forced to sit as the man fumbled with the GPS, forced to encounter the full, dull reality of this person. He sat back and closed his eyes.”

Less successful is the perspective reversal later on in the story, when we see Richard through the humble headmaster’s eyes: a prick with a full head of hair and the attitude of someone who hates being told “no.” It’s not entirely unsuccessful, but it’s a jarring and rough shift in a book full of much subtler moves, like the aforementioned father of “What Do You Do With a General,” who clearly beat his kids and/or wife at some point. Cline’s stories also lack a certain sense of humor, a lightness that’s abundant in Anna Dorn’s Vagablonde, released earlier this year. Vagablonde is a comedy, but it’s a similarly coastal vision of people adrift in the new millennium.

Both books are full of pills and professional aspirations: Dorn’s titular Vagablonde is a lawyer and an aspiring rapper (not too far off from Taylor Schilling in Laura Steinel’s hilarious film Family), and throughout the book she attempts to balance a healthy work life with a recklessly unhealthy artistic life, cleaving a wider and wider berth between what she wants to do and what she’s doing: destroying her life. The men of Daddy are not dead set for destruction like Vagablonde, they’re inert—they may be miserable, their kids may hate them, their ex-wives may just be voices on the phone who arrange school visits and vacations, their mistresses may have wildly different expectations than them, but ultimately, really, what are they going to do about it? Nothing.

Claude Chabrol, in the last decade of his life, was asked: “Why have you made so many films critical of the bourgeoisie?” His response: “The bourgeoisie are the way I show them in my movies, neither bad nor good. They make me laugh. Quite honestly and objectively they never were a hundred percent nice. Because they are scared of living. That's what makes them how they are. They fear the real life. That's what makes me laugh.”

Cline has a good eye for the dead-eyed residents of the Amtraks and Malibu mansions, all equally comfortable to the degree that they can go to a restaurant and not worry about the check. Because if you’re not happy then, what next? What if you find yourself living out “Once in a Lifetime” and tumbling into an existential abyss in the middle of your living room surrounded by a family you no longer recognize? What if the family you thought was coming to you doesn’t exist? None of the people in Daddy know what to do when their lives go astray—but neither does Cline. There’s a distance to these stories that isn’t just stylistic but personal. These are case studies, not real people.

—Follow Nicky Smith on Twitter: @nickyotissmith