In this lecture given to French film students in 1983, Orson Welles brings up a Picasso quote related to him by Léger: the French painter asked Picasso what he’d do if the fascists came and locked him up, without his tools. Could he paint? “I will paint with my shit.” Much of Welles’ lecture is spent dismissing the auteur theory and imploring this fourth generation of Nouvelle Vaguers to “try acting instead,” and that being a metíer en scene is not the glory or gratitude it’s made out to be. He argues against posterity, insisting it is as vain and misguided as pure crass commercialism.

Welles should’ve made more films, but others, including himself, got in the way. But he was never a two-faced snob or a meek self-deprecator who stabs everyone in the back. What Welles said about Woody Allen—“I hate Woody Allen physically, I dislike that kind of man. He has the Chaplin Disease; that particular combination of arrogance and timidity sets my teeth on edge. Like all people with timid personalities his arrogance is unlimited”—fits Charlie Kaufman like a body glove. Fortunately he’s not as prolific or exhibitionist as Allen.

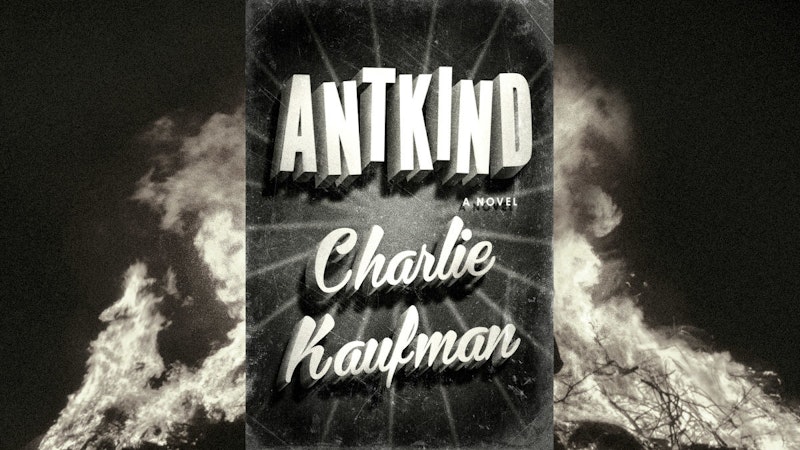

Kaufman wrote a couple of good movies (Being John Malkovich and Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind), and then he made a masterpiece in 2008: Synecdoche, New York remains hilarious, overwhelming, bewildering, deliriously sad, and immensely inspiring. But he hasn’t done anything since then. There was Anomalisa in 2015, but that was based on an old play. Kaufman’s new novel Antkind is his first major work since Synecdoche. It sucks.

The book is 700 pages, and follows B. Rosenberger Rosenberg, an asshole film critic with a bald head, big beard, and a giant port wine stain underneath. At the start, he’s toiling in obscurity, bitter of those with success and talent, neither of which he possesses. Rosenberg is an over the top perforative male ally: he never lets you forget about his “African American girlfriend,” or his personal pronouns (“thon/thonself”). Throughout the novel, he takes up dozens and dozens of paragraphs worth of words explaining how this or that statement could be misconstrued to be sexist/racist/what have you.

During a research trip in Florida, Rosenberg meets an elderly man in a rundown motel named Ingo Cutbirth. Rosenberg is a prick to the guy at first, and when Cutbirth tells him about a film he made, Rosenberg struggles not to laugh. Of course, then he considers the fact that Ingo Cutbirth is, in his words, "an undiscovered African American filmmaker." Rosenberg imagines how he can mention his girlfriend, or how he could take advantage of this man's legacy should he have anything to leave behind. We have to spend 700 pages with this guy. Turns out Cutbirth is a 119-year-old anomaly, the creator of a three-month long untitled film shot over the course of his life. Rosenberg is entranced, and watches it all with Cutbirth on a strict schedule. Days and nights disappear and the line between reality and the film blurs further still.

Then Cutbirth dies. Mesmerized by what he experienced, Rosenberg gathers all the reels, buries Cutbirth, and loads the film into a U-HAUL and starts driving back up to New York, eager to make his legacy off of the work of a genius, “brilliant undiscovered African American filmmaker.” Rosenberg has already written a book about William Greaves, director of meta-classic Symbiopsychotaxiplasm. This is his chance for a legacy. As he ponders how he will execute the Cutbirth estate while eating a burger at a rest stop, the truck catches fire, all of the nitrate film erupting in smoke and flames, and Rosenberg foolishly tries to salvage Cutbirth’s life’s work, but only ends up with brain damage and a single frame of the movie.

As the novel goes on, a similar structure and rhythm to Synecdoche, New York plays out, with Rosenberg seemingly spending decades of his life lost in a magical realist labyrinth of externalized neuroses and absurdist touches (Kaufman still excels at some of this: when Rosenberg obnoxiously asks if Cutbirth has ever read one of his most obscure film monographs, Cutbirth immediately replies, “Of course. It’s on my nightstand.”) Rosenberg tumbles through a world of cruel people and blind bureaucrats that are slaves to broken technology: "Slammy's," the burger chain where Rosenberg eats right before Cutbirth's film combusts, eventually takes over the world Amazon-style, without any Jeff Bezos stand-in. The future of Antkind resembles Philip K. Dick at times, both impossibly complex and dirty and neglected. A lot of the imagery in Antkind is easy to see on the screen, and most of it certainly isn’t “unfilmmable,” whatever the Kaufman says. He did it over a decade ago, he just needed $20 million.

Kaufman fills this book with boilerplate “SJW” parody that, ironic or not, makes Antkind a particularly tedious and enervating experience. Kaufman’s not a great writer, at least not here—a lot of it reads like bootleg Philip Roth. A good 200 pages of the book could pass for an undergrad’s imitation of Sabbath’s Theater, but Rosenberg is a tad tamer than Mickey Sabbath, only sniffing his femdom Tsai’s panties, not licking shit out of her asshole. In more ways than one, Antkind comes up short.

Cutbirth's untitled film at first appears to be an indictment of comedy itself as a malignant and evil force that must be stopped, and Kaufman's own attitudes toward mass entertainment aren't difficult to guess or Google. Sure, he's done punch-ups on Kung-Fu Panda 2 "to pay for his mortgage," but Kaufman, along with his Rosenberg, shrink away from popular culture because they find it beneath them, despite being to pathetic and weak to offer an alternative or simply live one out. They are participating in this culture they so despise and condemn. If Antkind is self-immolation, he certainly never breaks character: is this book meant to make fans of Kaufman's earlier work reconsider even that? Is that bad? On purpose???

Jon Mooallem’s profile for The New York Times Magazine, “This Profile of Charlie Kaufman Has Changed,” is interesting, and Kaufman comes off as a neurotic, incoherent snob: “I would like to have money that I don’t have,’ he replied, ‘and I tell myself that I could write a commercial blockbuster.’ But he also understood that he might be flattering himself; he’d never actually tried. He was proud of his commitment to do original, meaningful work. ‘There’s lots and lots of garbage out there that isn’t honest and isn’t trying to help clarify or explore the human condition in any way,’ he told me, ‘and it sends people down the wrong road’—skews our perceptions of our own lives, and each other—‘and it’s mind-numbing and it’s toxic, and I don’t want to have that on my résumé. I don’t even mean my professional résumé, but my résumé as a human being.’”

Give me a fucking break. Kaufman and B. Rosenberger Rosenberg don’t differ much on their pop culture opinions—Kaufman is just less effusive and crude. When Kaufman dismisses the idea of ever writing a “big action movie,” he has no idea what he’s talking about, because he doesn’t watch them. He’s obsessed with posterity and “honesty” and “integrity” in his work to the point of not producing work. Buzz off, then. I look forward to his Netflix film, I’m Thinking of Ending Things, in September. He said in that Times profile that he approached it as his “last directing job.” Go ahead and quit if you don’t want to try. Kaufman says he attempted to get into television in the last decade and couldn’t get anything off the ground. Why stop now?

Antkind blows, maybe because Kaufman refuses to paint with his shit. Everything in it is overshadowed by a constant, stupid, one-note, joke about male allies. Film references abound, but Kaufman's daft wordplay and obvious disdain for most of what constitutes film history make this an incredibly boring read. About 400 pages in, there’s a long Donald Trump dream scene: the President has a robot designed to match him exactly, and he makes love to it. This goes on for a dozen pages. This material is beneath The Daily Show. There’s even more Trump material as you go on! Every stupid cliché about Trump being vain, grotesque, and gay is in there. It made me want to bang my head against my desk, because there are streaks of brilliance in Antkind. I just don't think that they would take up more than a dozen pages.

Synecdoche dipped into Jungian gender reversals and doubling, but it wasn’t weighted in the malaise of topical discourse. Antkind is of a piece with “#Resistance pulp,” whether it’s by Richard Wolff, Bob Woodward, James Comey, John Bolton, or Mary Trump. Kaufman, at 61, has nothing left to say about art or the human condition, and he’s wasted 700 pages making fun of or embracing a hackneyed and annoying contemporary stereotype, offering almost nothing but more “adorkable” absurdism that works on the screen, but not the page. There’s nowhere to go for him here: you can write about Rosenberg shrinking and being reborn and screwing mermaids and marrying clowns and trudging through millions of bodies in an apocalypse, but it’s not the same as simply seeing it. Kaufman isn’t a good enough writer to make this material compelling with words alone.

—Follow Nicky Smith on Twitter: @nickyotissmith