One of the most prolific and multifaceted talents in modern pop music, Van Dyke Parks has managed to accrue an unbelievable resume and consistent categorization as a genius while remaining relatively unknown to a wide audience. As a lyricist for the Beach Boys’ aborted SMiLE record (as well as the finished version released by Brian Wilson in 2004), an arranger, producer and studio musician for artists like U2, The Byrds, The Everly Brothers, Randy Newman, Tim Buckley, Phil Ochs, Frank Black, the dB’s, and countless others, Parks has taken part in some of the most innovative and popular recordings of the last 50 years.

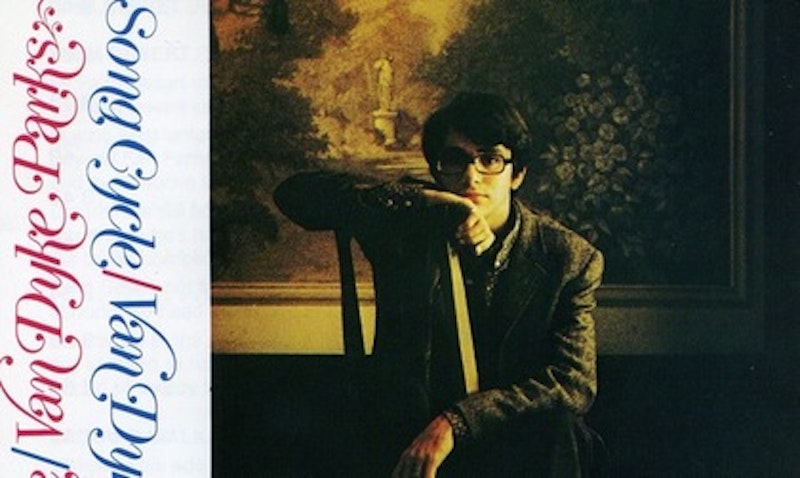

His solo career, which started with the release of Song Cycle in late 1968, has been no less influential. Composed and recorded in the wake of SMiLE’s dissolution, Song Cycle was the most expensive project yet bankrolled by Warner Bros. records; that the label would entrust that kind of funding to a then-24-year-old unknown solo act speaks to the faith they had in Parks’ vision, and he did not let them down. Song Cycle is a 32-minute inclusive look at American music, from ragtime and bluegrass through musique concrète and SoCal pop. Its effect on later generations of musicians can be seen in testimonials from Thurston Moore and Jim O’Rourke, or in the far-reaching Americana of newer acts like Joanna Newsom, whose record Ys boasts arrangements by Parks himself.

Splice corresponded with Parks through email around Song Cycle’s 40th anniversary. His most current project is An Invitation, the recent record by The Bird and the Bee singer Inara George. Parks was quick to dispel some of the myths surrounding Song Cycle’s funding and initial reception, and to place its music in the larger pop context of the time.

SPLICE TODAY: The stories surrounding Song Cycle are legion—that it was the most expensive record yet made at Warner Bros., that it was an infamous commercial flop upon first release, that you started it after the Beach Boys' SMiLE sessions fell apart—but what was it actually like to be in the studio? Did you feel pressure because of all the label funding, or was it just a really fun, creative time with [producer] Lenny Waronker and the session musicians? Something in between?

VAN DYKE PARKS: Song Cycle wasn't really such “an infamous commercial flop on first release” as you characterize it. The ad campaign that followed its release was to close the gap between great expectations and nominal sales. [Warner Bros. took out print ads to poke fun at the record’s cost --ed.] Still, there was every expectation that the recording costs would be recovered, and they were, within three years. Profitability on an LP album with no songs to promote on teenage AM stations (FM radio alternatives were nil at the time) were slim. I neither felt nor imagined any “pressure.” I knew Lenny Waronker had received a real education in studio procedure, and his boss knew that was essential to the growth of the label.

ST: There's an obvious effort on Song Cycle to include all genres of American music, from Appalachian folk to gospel and show tunes up through Randy Newman and Donovan. And yet the title is pretty modest, considering the ambition; you could have used "Discover America," for instance, which you saved for your second record. Was the "tour through American music" idea really present in your mind, or is the album's eclecticism merely indicative of your wide-ranging tastes at the time?

VDP: There was no “obvious effort on Song Cycle to include all genres of American Music.” Any stylistic variety in the work is a natural product of my wide experience (at age 24) of many musical genres. I was just following my own understanding of what music could reflect.

Aaron Copland (who'd given me an A in a collegiate test) was once asked, “What is American music?” He answered, “American music is music that was written in America.” I believe that explains the penchant that some music observers have for branding Song Cycle “American.”

ST: What were your immediate influences on Song Cycle, both lyrically and musically? There's a similarity to Copland in the use of American idioms in orchestral settings, just as there's a little Whitman in your variety of characters and place names. But your work is more elliptical than either; what were the formative influences on that record?

VDP: Lyrically, the free-relating lyrics were consciously influenced by the Beat poets, James Joyce, Ferlinghetti, e.e. cummings, with perhaps a nod to Bob Dylan—the latter of whom set a new elastic standard in what a song lyric could achieve.

The music? Basically an attempt to integrate the power of Cliché into a Pop arena. By “Pop,” I mean a style of expression stamped in the Visual Arts during the sixties (Warhol, Lichtenstein, Rauschenberg, etc.) in which images are reduced to the irreducible redux. In Song Cycle, such images are in orchestral detail (the Presidential dirge in the march to “The All Golden,” the street sensibility in “Laurel Canyon” with the honk of the Helms Bakery truck, the flatulent horn retorts underscoring the Gershwinesque “I came west unto Hollywood.”

ST: David Anderle, in Paul Williams' book Outlaw Blues, says that Brian Wilson “felt Dylan was placed in the music scene to end music. He thought musically he was very destructive.” Naturally, Wilson was being a little facetious and had a lot of respect for Dylan, but I can see where their sensibilities would be at odds with one another. They represent a sort of schism that was happening at the time, between the artists who were working backwards, towards more of a folk primitivism, and those who were pushing pop forward towards a more orchestral, musically learned stage. It's the difference between Neil Young's one-note solos on Everybody Knows This Is Nowhere and the arrangements of Pet Sounds: both innovative, but one's defiantly minimal where the other is impeccably arranged and expansive. In the latter group, I'd also put some of the later Beatles, maybe Randy Newman and Harry Nilsson, and Song Cycle. Did this ideological divide ever get discussed; were you even aware of it? Or was this all happening at a subconscious level?

VDP: I've never discussed [that] (in the way you frame things as an “ideological divide”) with anyone. However, I do disagree with Wilson on Dylan. Dylan's musical iconoclasm didn't shock, threaten, or annoy me. I'd had experience with sprecht stimme (speaking voice), through early childhood exposure to German music that validated it. At age 12, I sang “Pierrot Lunaire” by Schoenberg, and by that time, probably knew The Threepenny Opera by heart.

As for Dylan? I forgive him for his success in leading the counter-culture and all it brought to music. Yesterday, I played with him and Ry Cooder as a trio, in a filmed performance for a PBS production based on A People's History of The United States. We got along fine.

ST: You were a child actor before your music career took off. What was the deciding factor there? At what point did music become more exciting or interesting than, say, being on set with Grace Kelly and Alec Guinness in The Swan?

VDP: I needed money to go to a private school to study music (The American Boychoir, outside of Princeton, N.J., from '52-'57). My acting jobs fulfilled the tuition needs. That was the extent of my interest in acting.

ST: Song Cycle’s sales numbers were pretty grim, yet that didn't appear to have much effect on your career or your relationship with Warner Bros.—you went on to work with Randy Newman, Cooder, Judy Collins, Phil Ochs, Gordon Lightfoot, and then released your second album (which if anything was even less immediately commercial than Song Cycle) in 1972. Do you think labels like Warner Bros. were more supportive of risk-taking artists at that time, or is that just a rose-colored myth that later generations have about the era?

VDP: There you go again, John! This time, with “pretty grim.” I reject your characterization. I was happy to produce Randy Newman and Ry Cooder, which, with other artists, provided a social grace and aesthetic proving ground.

I was interested in supporting artists who were curious, totally "interested", rather than seeking to be “interesting.” It's a personal character mark I seek in artists I support to this day.

ST: How about the rumors of a forthcoming reissue and remaster of your solo debut?

VDP: Song Cycle indeed seems destined for 5.1 surround.