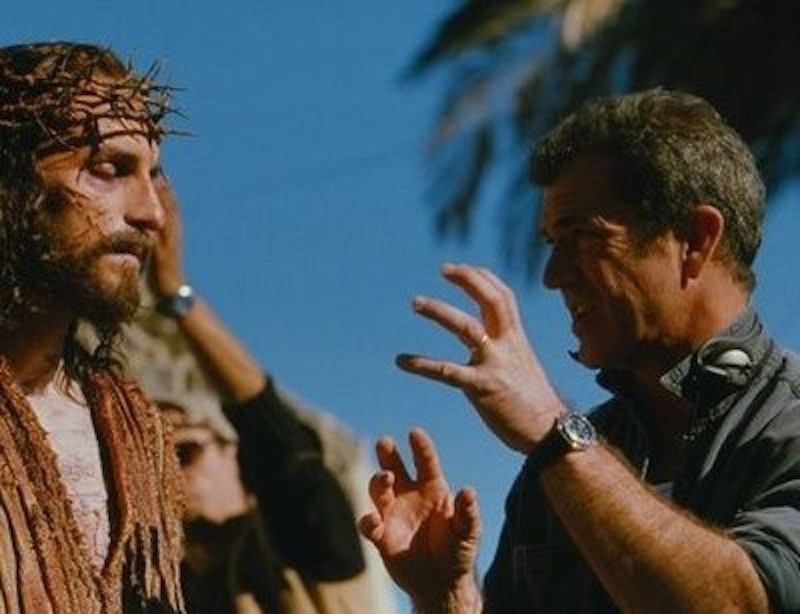

Mel Gibson is having a comeback. The director, who’s gotten into trouble in the past for anti-Semitic comments and drunken behavior, has a new film out, Hacksaw Ridge, which has been critically acclaimed. He’s also planning a sequel to The Passion of the Christ, his blockbuster 2004 film about the crucifixion of Jesus Christ.

I have a pretty good guess as to what Gibson it planning for the sequel to The Passion. It involves a rich but heterodox interpretation of Holy Saturday, the day between the crucifixion and the resurrection. If Gibson is going in the direction I think, the film could be a powerful drama that touches on the human psyche as much as traditional Christian theology—in fact it could impress and move secular audiences even as it confuses and annoys Christians.

Recently, Lakewood Church pastor Joel Osteen asked Gibson if the movie would be about the resurrection, and Gibson replied, "Yeah, I think so... We were talking about it. We're getting into some interesting areas on this that, between the Crucifixion and the Resurrection, like, what was going on in there.” Gibson added, ”You do it so that it surprises," he said. "You do it so that it enlightens. Just some kind of telling, some kind of rendering that suffices is just not good enough. It has to be dug deep for and it has to have, in its image and its sound and its visual, it has to be able to delve to places that people have never even thought before, I think, on a theological level.”

There’s a theory in some theological circles that after the crucifixion Christ did not, as traditional Bible scholars believe, simple descend into hell to free lost souls. Rather, Jesus endured “a second chaos,” a period of absolutely despair and darkness where he became sin itself. The main author of this idea was the Swiss theologian Hans Urs von Balthasar. Balthasar argued that the crucifixion and death of Christ is the locus of the judgment of God for all humanity. He argues that Christ in hell becoming the accursed one who is sin personified; Christ goes to the place where “the smoke… goes up for ever and ever,” as described in Rev. 19:3 in reference to the eternal destruction of Babylon. He is thrown into the lake of fire that’s the second death. Referring to Christ’s condition, Balthasar says, “This is the essence of the second death: that which is cursed by God in his definitive judgment sinks down to the place where it belongs. In this final state there is no time.” Balthasar once said that the “real object of a theology of Holy Saturday does not consist in the completed state which follows on the last act of self surrender of the incarnate Son to his Father… rather… it is something unique… all the sins of the world now experienced as agony and a sinking down into the ‘second death’ or ‘second chaos.’”

Balthasar’s idea has caused controversy and disagreement among theologians, who claim that Christ attuned for our sins by dying on the cross, and that was enough. But as drama, delving into the unorthodox interpretation of Holy Saturday is a brilliant idea. Gibson is perhaps offering a chance to genuinely break new ground in a cinematic interpretation of the Christian story—an interpretation that can appeal to all audiences because it explores the human psyche as much as Holy Writ.

Most Christian films have become redundant because they’re either a re-telling of previously told Bible stories—witness the box office disaster that was the recent Ben-Hur remake—or they’re syrupy and simple-minded affirmations of God fighting political battles or working miracles. A film based on Balthasar could truly be different. In fact, such a film, or films, have already been made. The film noir movies of the 1940s and 50s presented a shadowy, subconscious world where the hero often became so tainted with sin and compromise that he becomes an “antihero,” only to emerge with a deeper understanding of his limitations and human nature. In an 80s remake of the noir show The Untouchables, the character Eliot Ness says, “I have become what I beheld.”

In his wonderful book Pictures at a Revolution: Five Movies and the Birth of the New Hollywood, Mark Harris documents how in 1967 Hollywood underwent a revolution when traditional films were supplanted by movies of challenging psychological insight. In the Heat of the Night, the 1967 Academy Award winner for best picture, places the viewer in a dark, dangerous world that’s an analog to a descent into hell and Balthasar’s second chaos. It’s the 60s and black Philadelphia detective Virgil Tibbs, his name an obvious reference to Dante, finds himself struck in Sparta, Mississippi where he’s asked by the local police to help solve a murder. Tibbs obviously represents virtue along the racists of this underworld, but what makes In the Heat of the Night remarkable is that Tibbs’ own racist tendency makes him (temporarily) accuse the wrong man of the crime. Tibbs, like Christ on Holy Saturday, must become sin itself, the thing he came to cure.

Modern films are replete with heroes who travel to the underworld and take on the aspects of sin in order to save their world. In gangster movies like Donnie Brasco and The Infiltrator, the protagonist goes undercover and underground, often reaching a point of chaos and confusion where he’s not sure what is right or wrong or where his loyalties lie, only to emerge intact at the end. In the Star Wars mythos, Luke Skywalker travels deep into the dark interior of the Death Star to battle his father, Darth Vader, who has been lost to the Dark Side of the Force. At on point Skywalker falters, becoming consumed with so much rage and hatred that he can do nothing but pound Vader into submission. In the best scene in 2008’s The Dark Knight, Batman descends beneath the overpasses of Gotham to battle the Joker, a demonic villain whose only goal is “to watch the world burn.” The Joker and Batman are similar, two “freaks” driven to underground extremes by trauma. This isn’t true, as Batman is a virtuous crime fighter; it only seems that way, as the Dark Knight has donned the black costume of evil, an outfit normally reserved for characters like Dracula, to fight evil. In short, Bruce Wayne has become sin and gone below the surface in order to resurrect his city.

If Gibson is planning something similar for his sequel to The Passion of the Christ, he could be on to something rich and profound.