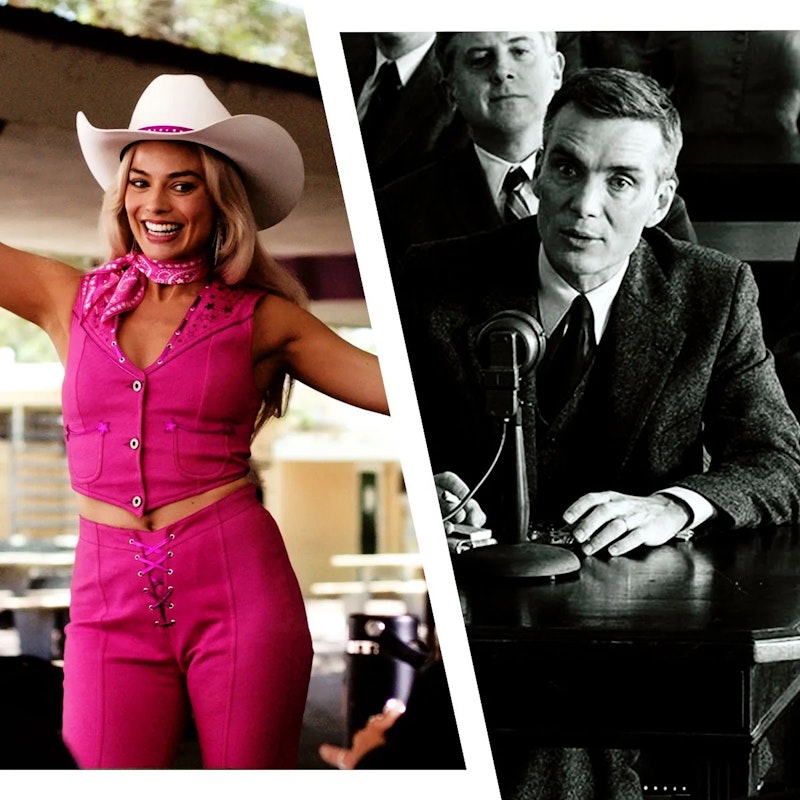

The hype around “Barbenheimer” feels like a return to normal blockbuster summer movies. The diametrically-opposed Oppenheimer and Barbie releases landing on the same day was fortuitous, especially as cinema remains plagued by sequels, remakes, and reboots. The excitement around their release led to many on social media, including me, planning to see both on the same day as a celebration of their pending mood swings. What I didn’t anticipate was the common theme of existential crisis, but perhaps I should’ve seen it coming.

Oppenheimer begins his story as a student struggling under rigors Cambridge’s chemistry program, so thoroughly broken that he attempts to poison his tutor. As the film takes us through his career, it’s against the backdrop of European autocracy’s devastations of the Jews, which is treated as American academia’s gain. The other background character is the Red Scare, and those dabbling in communism in close proximity to Oppenheimer, including his wife, mistress, and brother. After the Pearl Harbor attack and German scientists splitting the atom, Oppenheimer and his colleagues find themselves in a race against the Nazis in developing an atomic bomb. After the war, Oppenheimer learns the hard way that he was always expendable to the government, especially as questions about what communist sympathies might persist in relation to his ongoing research, while also dealing with the internal conflict of his invention’s impact.

If Oppenheimer is always pushing past angst to get the job done, Barbie is greeted by ennui as a sort of anti-epiphany. Existing in a world of cheery matriarchy, Barbie fails to notice Ken’s longing, secure in the knowledge that her world will exist as it has always existed, until, mid-dance number, she wonders what happens when we die. Soon plagued by flat feet and cellulite, Barbie discovers these are the results of her real-world kid becoming increasingly distraught. When Barbie and Ken journey to the real world, she’s greeted by harassment, while Ken stumbles upon male empowerment at the library. Barbie’s real-world kid turns out to be the kid’s mother, taken for granted by her c-suite male bosses at Mattel and struggling for relevance in the eyes of her tween daughter, who turns to doodling moody Barbies as an outlet. When Ken brings his patriarchal discoveries back to Barbie world, a battle of the sexes ensues, where both Barbie and Ken learn what brings meaning to their lives.

The directors of both films have made no secret that they see their stories as reflections of contemporary society. Christopher Nolan sees Oppenheimer as a building block of an answer to the questions of today’s diplomacy and warfare, and questions of general respect for the scientific community. Greta Gerwig has described Barbie as a broad metaphor of adolescence, where girls are thrust into womanhood’s conundrums, double-think, and paradoxes.

Oppenheimer fares better, even if it still feels lacking. Because it’s a period-piece biopic, Oppenheimer has a clear advantage in arguing for its timeliness. There’s been some criticism of its handling of women and minorities, but, as it ends around 1959, there’s a point where it’s a realistic portrayal of its time. When he’s completed his tenure at the Los Alamos Laboratory, Oppenheimer expresses surprise that the land won’t be returned to the indigenous people it was taken from. One of the lowest points might be that his affair with Jean Tatlock, a communist organizer, is treated as a salacious MacGuffin. The other low is how it glosses over the civilian impact of the atomic bombs dropped on Japan, especially when this appears to be a reason for Oppenheimer’s evolving views on the burgeoning military industrial complex.

The most frustrating thing about Barbie is that begins a lot of interesting thoughts it can’t finish, and the thoughts it does finish are weighed down by utopianism, openly admitting to not knowing how to end the movie. Barbie’s discovery of the all-male board of Mattel starts interesting, but doesn’t lead to much. This should’ve been a cause for greater surprise when they arrived in Barbie world. For all the film’s purported feminism, the most interesting moment was Ken soliloquizing over his search for purpose in his life, and trying to figure out what it means to be a man who was designed in reference to a woman. And perhaps it’s the effect of watching Oppenheimer earlier in the day, but the Barbies manipulating the Kens into war felt more like ugly imperialism than female empowerment.

If Oppenheimer and Barbie are messy around discussions of war, peace, and sex, then they’re certainly achieving that particular angle of reflecting contemporary society. Despite taking place before much of its younger audience was born, Oppenheimer’s own demand to explore the consequences of war remain prescient as ever. Barbie’s approach to gender politics might not resonate with everyone, but in spite of what conservative critics have said, I don’t think there’s any intended malice. I’d say that Ken is an excellent stand-in for young men struggling to find their sense of direction in the world.

One of the better parts of this experience was people-watching at the theater. More teens and young adults turned out for the 11 a.m. Oppenheimer screening than I expected, and it was great to see so many girls at Barbie with their mothers and grandmothers. I hope the box office success of last weekend gets Hollywood out of its lazy rut to return to making movies that are original and fun.