His favorite words were “schmuck” and “putz.” He walked to the mailbox shirtless in torn undies, without shame or embarrassment. He was cantankerous, outrageous, mean and cynical. Yet he could be charming and generous and regale you with dirty jokes. He was old school Hollywood, a movie legend who played an important part in reviving 1970s American film.

I met Frank Yablans in his later years when he lived next door to the guesthouse my wife and I rented in the Hollywood Hills. He’d gone through two divorces and was living with his girlfriend Nadia. I became friends with Nadia and got to know Frank. I made the mistake of telling him I was a screenwriter.

“You mean you’re a schmuck,” he said.

I was taken aback.

“All screenwriters are schmucks. They think they know more than anybody but someone else always profits from their work.”

“That’s pretty cynical,” I said.

“It’s also fucking true, you putz. I’ve been making movies my whole life and one thing has never changed. Writers write but producers make the money. That’s why they call it show business.”

“Doesn’t that bother you,” I asked. “Shouldn’t writers profit from their work? They’re the ones who pour their heart onto the page.”

“If you want to know how the film industry works,” Yablans said, “there are only two movies that tell the truth. The Bicycle Thief shows you there’s no morality, that the world is dog eat dog and survival of the fittest. And The Godfather shows you the politics of power. You know, ‘Keep your friends close but your enemies closer.’”

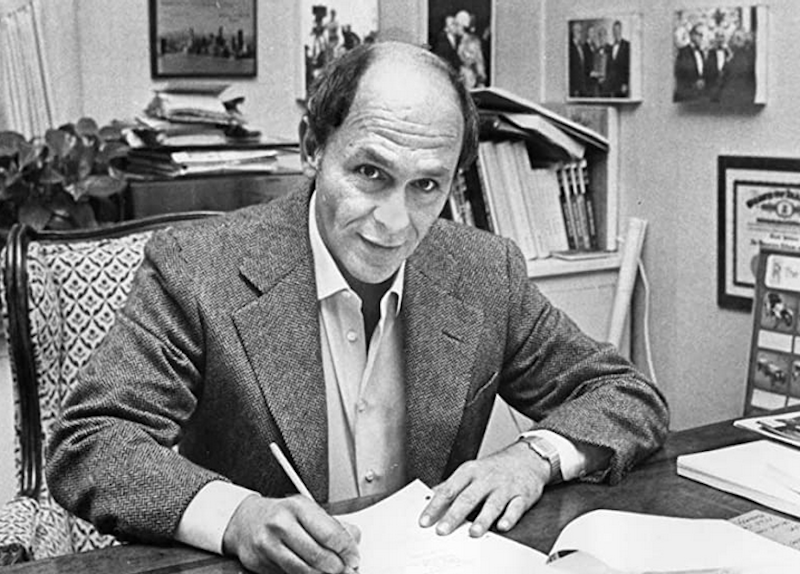

Yablans would know. He played a major role in the success of The Godfather. As head of Paramount Pictures, he changed the way films were released. Rather than slowly exhibiting a film in Los Angeles and New York to build word of mouth, he went nationwide with 1000 prints in the second week. This was radical, especially since the film was three hours long. The strategy worked and The Godfather became a hit. Jaws emulated the tactic in 1975 and the entire industry followed suit.

Yablans wasn’t afraid to micromanage a film’s release. On Christmas Day 1972, he chewed out the owner of a Washington, D.C. theater for underselling The Godfather by $2 a ticket. The man had just left the hospital after suffering a heart attack.

As studio head, Yablans ran a tight ship. The first thing he did was merge publicity and sales. He fired hundreds of employees and set up a system where “all roads lead directly to my office.” He gained a reputation as an autocrat with a Napoleon complex. (He was about 5' 6.") He embraced his image. “That’s the only way a dumb schmuck like me became head of Paramount. It’s easy to be humble if you were born a prince. I came from a ghetto.”

Yablans was born in Brooklyn in 1935. His father drove a taxi while his older brother Irwin later became a film producer. (Irwin produced Halloween in 1978.) Yablans’ first job, at 12, was plucking chickens in a Brooklyn meat market. He graduated high school and then served in the army. He got his start in Hollywood selling films to US theaters for Warner, Disney and Filmways. He distinguished himself by focusing on minutiae like the physical contours of each theater. When marketing the Godfather, he turned down certain theaters because they were too narrow. “It’s a three-hour show, and I didn’t want people getting claustrophobia.”

In the late-1960s, Yablans became executive VP of sales at Paramount. His marketing acumen led Love Story to become the highest-grossing film in 1971. That year, he became president of Paramount at 33. His four-year tenure revived the studio and oversaw the release of Chinatown, Paper Moon, Harold and Maude, Serpico, The Godfather and Godfather II.

Godfather producer Albert Ruddy said, “Frank was opinionated and sardonic but he was always the smartest guy in the room.” One of Yablans’ aggressive opinions included wanting to cut 30 minutes out of The Godfather so theaters could have more showings. Robert Evans, Paramount production chief, pushed back and the studio released the longer version. Ruddy credited Yablans for having enough humility to change his views. “He was a genius about distribution,” Ruddy said. “His approach led to lines around the block.”

“When you’re the president of a movie company,” Yablans said, “you don’t enjoy much interplay with creative talent. You’re isolated from them. The way I ran Paramount was the least devious way in the world. It was either yes or no, right off the bat, and 90 percent of the time the answer was no. Someone has to play the heavy.”

In Peter Biskind’s book Easy Riders, Raging Bulls about 1970s American film, Yablans was portrayed as a money-grubbing villain with self-esteem issues. Paramount executive Peter Bart recalled an evening with Yablans in London. “We were going out for dinner. I picked Frank up in his room. He was finished dressing, looking at himself in the mirror, and he said, ‘You know, I’m a really ugly man, I’m a homely fat Jewish man.’”

I asked Yablans about his depiction in the book.

“What upset me is that Biskind wrote I had a huge ego and that Robert Evans and I hated each other. That’s bullshit. We worked together to keep the artists in line. Coppola was the one with the gigantic ego. I never made a picture over $6 million except Godfather II and that was a total indulgence Coppola made for himself. When he made Apocalypse Now, I was disgusted. I told him his penchant for overspending would ruin his film career. And you know what, it did.”

In 1974, Paramount released Chinatown. Yablans had an intense fight with Evans over deal terms. Evans had negotiated a large piece of the gross but Yablans wanted to share the cut 50–50. Charlie Bludhorn, CEO of Gulf & Western who owned Paramount, took Evans side and Yablans was fired. He was replaced by Barry Diller. Yablans told me, “The only person I still hate to this day is Diller.”

After leaving Paramount, Yablans was given a contract by Alan Ladd at 20th Century Fox as an independent producer. His first film out of the gate Silver Streak (1976) was a hit. It cost $5.2 million and grossed $32 million in film rentals. A year later he released The Other Side of Midnight based on a book by Sidney Sheldon. The film was a box office failure, largely in part to Fox’s commitment to Star Wars. Yablans was an up-close witness to the changing trends in American movies.

“We went from original auteur inspired ideas to movies that could sell toys. I couldn’t sell my ideas anymore,” he said. “If your film didn’t make $100 million, the studios weren’t interested.”

Yablans went on to make The Fury (1978), North Dallas Forty (1979) and Mommie Dearest (1981). In 1983, he was hired by Kirk Kerkorian to save debt-laden MGM. Yablans reorganized MGM and United Artists into a single company but the stock value continued to fall. Ted Turner purchased the studio in 1986 and Yablans was again out of work.

“Hollywood loves two things: they like to see failure succeed and they like to see success fail. Mostly they like failure because when you think of it, most people out there have failed. So, somebody else’s failure makes them feel a lot more safe and secure. Somebody else’s success makes them crazy.”

Yablans enjoyed being an independent producer because it allowed him to work with writers. He received co-writing credit on North Dallas Forty. “It was based on a novel but the author [Peter Gent] had no idea what he was doing. He was an ex-football player and I think he took too many shots in the head. We shared writing credit but that script was all mine.”

When I met Yablans, he was running Promenade Pictures, a production company dedicated to making family-friendly animated films from the Bible. One day he asked me what I was writing. I told him I was working on a screenplay about angels.

“Jewish angels or Christian angels,” he asked as if trying to stump me.

“I’d have to say Jewish since they’re more active in human lives. Christian angels are pretty much just messengers, right?”

This triggered many conversations about spirituality and religion. Yablans confessed he’d come to believe Jesus was the Messiah the Jews had prophesied.

“Are you saying you’re a Christian,” I asked him.

“I’m saying Jesus was a Jew speaking to other Jews. I’ve read everything he was supposed to have said and I’m yet to see anything I don’t agree with.”

The more I got to know Yablans, the less he called me putz or schmuck. Still, he remained abrasive with others. Once when the pipes burst in his home and flooded the carpets, I overhead him cursing out the homeowner. He called the woman every expletive in the book. This was a taste of the ferocious Yablans that once ran roughshod in Hollywood.

I never took Yablans’ insults personally. He’d been a boxer when he was young. I viewed his bluster about screenwriters being schmucks as left jabs trying to keep others off balance. It probably helped him win many negotiations in his day. To me he was merely an aging neighbor with health issues. He was also a rare specimen like an albino cobra who you don’t get to see very often in the wild. He made me laugh even when he was offensive.

As the years passed, Yablans’ addiction to cigarettes caused him to suffer coughing fits. In 2012, he and Nadia moved to a condo in Marina Del Rey. His health problems worsened. He died in 2014 at 79. He took with him a small piece of old-school Hollywood that will never be seen again.