Should heroes be merciful? At the very end of Spectre, the evil Blofeld (Christoph Waltz) is badly wounded and helpless. James Bond (Daniel Craig) has the drop on him; Blofeld asked to be shot and put out of his misery. But instead, Bond hesitates, and then walks away.

If this is what mercy looks like in a Hollywood blockbuster, it's pretty feeble. Yes, the hero doesn't shoot the villain. But moments later, the bad guy is apprehended by MI6 and taken into custody. The demands of justice are served. In fact, they're arguably better served, since Blofeld can now be interrogated and maybe lead MI6 to other villains.

The sequence is presented as demonstrating Bond's superior morality and trustworthiness; earlier in the film M (Ralph Fiennes) burbles on sententiously about how having killed gives you the authority not to pull the trigger. But not shooting a helpless, incapacitated enemy who’ll be arrested forthwith; that doesn't seem like such a huge moral quandary. It’s the bare minimum acknowledgement of the rule of law, and the practical virtue of live informants over dead ones. Spectre wants to give Bond credit for mercy and judgment without forcing him to make any of the sacrifices, or hard choices, that mercy requires. The film says heroes should be merciful, but only if it's convenient, and only if it’s in accord with the harsher dictates of justice, and even of revenge.

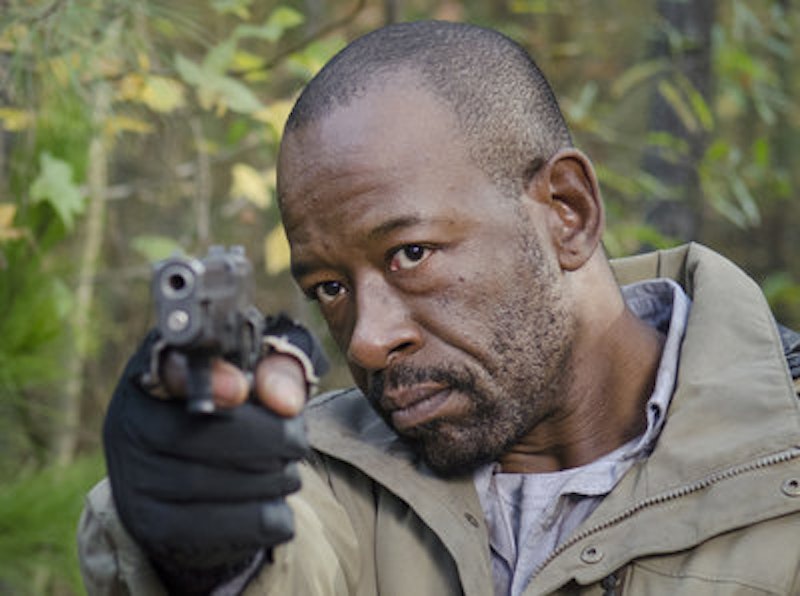

Episode 4 of the most recent season of The Walking Dead has a more sweeping vision of mercy. Titled "Here's Not Here," the show focuses on the backstory of Morgan (Lennie James), and attempts to show why he’s a devastatingly effective fighter and a virtuous man.

The episode begins after Morgan's wife and son have died in the zombie apocalypse. He’s traumatized, and obsessively kills zombies, and also murders two men who may or may not be threatening him. He stumbles upon Eastman (John Carroll Lynch) a former prison psychologist. Morgan tries to kill Eastman, but Eastman disarms him, and then (despite repeated attempts on his life) trusts him, and teaches him Aikido. Thanks to Eastman's mercy, Morgan is finally redeemed—though Eastman himself dies.

Bond's act of mercy just substitutes one punishment for another. Eastman forgoes punishment altogether, in the interest of humanity, and a narrative of hope. Still, that hope is contingent. Morgan isn't Blofeld; he's one of the stars of The Walking Dead, not one of the villains. Eastman is a psychologist, and he's presented as having rare and powerful insight into human nature. He sees that Morgan is damaged, but salvageable. Eastman, and the audience, both know Morgan is one of the good guys.

The calculus when dealing with evil people has to be somewhat different, though the show is ambivalent about what exactly that means. Zombies are beyond the pale; there are some people who can't be rehabilitated, and must be killed. Eastman himself, we learn, before the apocalypse, killed the psychopath who murdered his family, though he says it gave him no peace. And Morgan (in a frame sequence) keeps a captive locked up, rather than opening the cage, as Eastman did for him. The episode endorses mercy when you're dealing with decent people who’ve done bad things. But there are also bad people out there… and the episode ultimately seems to conclude that extending mercy to them is impractical.

Nora Olsen's YA gothic suspense novel Maxine Wore Black does the impractical. The title character, Maxine, is a psychopath and a domestic abuser. She killed one girlfriend, Becky, and threatens her new girlfriend, the narrator, Jayla, as well. At the end of the novel, Maxine and Jayla are trapped together in a burning house, and, as Jayla says, "I thought about leaving her behind to get burned to death. I really did. It would serve her right, wouldn't it?"

Jayla adds, "But I'm not that type." Maxine deserves death; she's an unrepentant murderer, and a selfish, cruel person. But Jayla is not someone who murders. She pushes Maxine off the roof—to save her, not to kill her. Jayla is a person who chooses mercy, regardless of whether the person receiving the mercy is deserving or not.

Maxine doesn't go to jail for her crimes—in part because Jayla, who, as a trans woman, has had personal experience with the police and doesn't trust them, believing they’re unjust. The choice is not between killing Maxine and putting her in jail, as it is for Blofeld. Nor does the act of mercy change Maxine, as it does Morgan. Maxine doesn’t repent, and at the end of the book, she's a creepy, selfish, stalker, just as she was at the beginning. It seems possible that Maxine will go on to stalk someone else, and while it's not very likely that she'll murder again, it’s possible.

So was Jayla cowardly to not kill Maxine when she had the chance? Was she wrong not to go to the police? Isn't mercy in this case a moral failure? Maybe so. But on the other hand, if mercy has any meaning, it needs to raise those question. When mercy is just choosing between forms of punishment, or when it's just recognizing goodness, then it's not really mercy. It's justice. And US popular culture loves justice, with the good guys always winning. Stories like Nora Olsen's, in which the narrative embraces mercy instead of, or as an alternative to, justice, are much rarer—and therefore much more valuable.

—Follow Noah Berlatsky on Twitter: @hoodedu